Volume 2, Number 2 2009

T.M. Göttl

BLADE OF THE KNIFE

On the day when we lost

the battle for the trees,

the man in the bank teller window

removed his sunglasses,

and I saw the children born of sand and glass,

caged inside his irises.

He passed me a knife and a lit cigarette,

and dismissed me in the language

of volcanic ash.

On the day when we lost

the battle for the waterfowl,

I smoked that cigarette,

waiting for the bus. Amid the orchids and

the fractured yellow sundresses,

pigmented characters crawled across my hands,

telling me

that I could see the future.

On the day when we lost

the battle for the wheel,

I sat in the wooden corner of a courtroom pew,

discerning the future in the blade

of the knife.

A sepia-toned girl,

wearing a jumper and pale gray eyes,

had stolen something from me, smuggled

under her jacket, and she ran, laughing.

On the day when we lost

the battle for the rivers,

I shared the railroad tracks

with two stray dogs, named after Viking gods;

black and white, my forestep and my shadow.

Barefoot now, my shoes long since pawned

for icons and faerie tales, I faced the west

and the cooling sun, waiting for the final train

to the settlements. The knife

fell from my pocket, shattering

into one hundred silver windows,

the many-colored eyes

of presidents and refugees.

CHALLENGE

Black water, axes, corroded circuits—

I’m an invalid, watching streetlamps melt a

limping incandescence

across the asphalt,

tracing my finger along purple contours—

horizon, workplace, pregnant clouds.

Hail Mary, full of grace,

the Lord is with thee.

The jazz organist rolls his upright piano

across the intersection,

singing for the broken,

singing for the unconfirmed,

singing before the harbor announcing

our severed city,

scratching out stories

of the plaster ghost haunting the tower,

and the children at war, always the children

at war.

Blessed art thou amongst women,

and blessed is the fruit of thy womb.

Buttonholes unravel, and black corsages

kneel in the road, with the

dirt and the blood and the money.

The psychology generals intercept

oaken doors, hiding

in their picture book warehouses,

initialing contracts to Shanghai and Luzern.

With darkened ears, they can’t remember

autumn or stale bread

or pushing the upright from

the decks of ships.

Holy Mary, Mother of God,

pray for us, sinners,

Seeking answers from storms at noon

and a five-piece quartet,

I replace icons with gypsy moths, knowing

that the elect, those who carve tattoos

across their arms and shoulder blades,

illustrating their unchallenged certainty,

have never really met God.

T.M. Göttl is a member of the Buffalo ZEF creative community, which published her poetry collection, Stretching the Window, in 2008. Her work has appeared in such publications as The Mill, Deep Cleveland, The Poet’s Haven, and The Hessler Street Fair Anthologies. She lives in Brunswick, Ohio.

Mary Ellen Derwis

Mary Ellen Derwis is the coauthor of JOMA–online, an online gallery of concrete poetry and photography. Her work has appeared in such publications as Otoliths, Oregon Literary Review, Bosphorus Art Project Quarterly, and Unlikely 2.0. She lives in Brecksville, Ohio.

Henry Hart

RETURN TO THE CHURCH OF THE HOLY VIRGIN

1.

When my fiancé didn’t come home from the bar,

St. Sebastian stepped from an icon on the mantel,

wrote a note with an arrow about Houdini’s artistry:

You must swallow the hairpin, throw it up quick

to pick the padlocks before you drown.

The day’s blue ink will erase him from the pantheon.

Most nights I could hardly swallow a sleeping pill.

My fingers shivered around tea cups,

stiffened to quills that couldn’t write.

The day he left, he muttered: “I’m sick of living

with chilblains and cabbages on this dead-end street.”

His lover’s car idled in the street. It was Christmas Eve.

Stars jutted like nail heads above the church.

An electric angel flickered on the crèche,

shadowing the plaster sheep and ass.

2.

Tonight I circle back like hands on the bar clock,

brush snow from paint scars of my former name

on the mailbox by the house we rebuilt together.

The church hasn’t changed. Candle flames

shudder in the same warped windows.

Plaster animals slump around the same dim crèche.

Leaning into wind, arms weighted with exotic gifts,

the wise men look as exhausted as before.

A gust scatters Christmas hymns over their heads.

It’s hard to know what Mary thinks—

her hands crossed over her breasts,

her eyes invisible under her white hood.

The electric angel illuminates the child

who looks up wildly at stars

glittering like compass needles in the night.

LYME DISEASE HALLUCINATION IN ST. FRANCIS HOSPITAL

After the blue-gowned man creaked by with his walker,

after the woman stopped moaning Baptist hymns to her dead petunias,

after snowflakes played their soft tattoo against my window,

the steel fang in my arm soothed me,

hunters with red torches galloped through a snowy field,

chasing deer toward a cliff the color of stars.

The ocean below caught them in rocks.

Waves tugged them toward the moon’s red ring

that incinerated their antlers like brush.

I stood on the cliff, wind scorching my tongue with salt and ash.

Behind me, snow thickened on swaybacked barns,

snapped ridgepoles over empty stalls.

An unsold cow shivered in corn stubble,

its hide a soiled sheet pulled tight around its ribs,

its breaths drifting into frost like gray feathers.

Three crows squawked on orange surveyor stakes.

A bulldozer choked, sinking its blade into gravel.

Skeletons rose from craters, bone by hammered bone.

When chainsaws sputtered, ghost deer slipped

through barbed wire rotting on gray fence posts.

Their teeth whittled our Christmas trees to spines.

By dawn, my pillow was thawed sod.

Inside my joints, the spirochetes of deer ticks

kept twisting like rusted corkscrews.

Henry Hart is the Mildred and J.B Hickman Professor of Humanities at the College of William and Mary. His poems have appeared in such publications as The New Yorker, Poetry, The Southern Review, The Gettysburg Review, New Kenyon Review, and Best American Poetry. He lives in Williamsburg, Virginia.

David Chorlton

TODAY

Little of note has occurred since the towhee

called from our neighbour’s tree

to attract attention to his silhouette

on the slender branch that holds him

every day against the sky

as it brightens, unless

we count the helicopters that hang

desperately over Madison

and only disappear after a gunman

is apprehended. The nights

have been peaceful lately, except

for the single shot we heard

just before eleven

as we said Goodnight

and turned over into darkness. It sounded close

but we concluded it was

someone else’s business out there where late

bleeds into later

and all the doors are locked. No mention

of an incident close to us came on

the early news, just the usual altercations

leaving casualties at dawn

in various deserted parking lots. We listen

daily to the plaintive notes some people drive

a thousand miles to hear. They say

there’s a truce; its daylight.

AN EAR FOR THE TRUTH

That a man would cut off his ear and give it away

was not questioned for a century

considering the unstable state of his mind

but after believing this version for so long

it comes as a shock to be told

that Vincent van Gogh’s friend Gauguin

most likely took the lobe with a stroke of his sword

in an argument’s heat. It wasn’t much of a story

to begin with, this account of making a gift

for a prostitute who seemed happy to accept currency.

The news lands in our midst like a sack

of potatoes on a peasant table, startles crows

out of a cornfield and causes stars to spiral

in the sky. Our challenge now is deciding what to do

about correcting the books on library shelves, in home

collections, kept as references in museums

or passed around a school class, not to mention movie

remakes or the jokes that don’t sound funny any more.

In time self mutilation may appear as unlikely

a theory as virgin birth or resurrection

although many will continue to discuss the artist’s

most irrational act as a significant moment

in painting history the way some Russians

still march for Stalin in Red Square on May Day,

holding his portrait and their fading banner

high because he represents a time their country was strong

or fundamentalists cling to a notion of the world

being created in a week or German soccer fans

say Hurst’s shot never crossed

the goal line in the 1966 game against England.

We all need something to hold on to;

sometimes a dictator is all there is. And if God

made the world it was for us to do with as we please.

As for that goal, it went in, I was there

and didn’t have to read the final score in all the papers.

Van Gogh could do what he wanted with his own ear,

he was never my favourite,

but let anyone say a bad word about Cezanne

and I’ll deny it even if I have to climb

Mont Saint Victoire and shout from its peak.

David Chorlton lives in Phoenix , Arizona. His work has been published widely in such publications as Cumberland Poetry Review, Hawai’i Review, Mississippi Mud, and Poet Lore.

Marina Rubin

LEAVING NEW DELHI

among mascaras and lipsticks, powders and make-up brushes, two airport security officers found my grandmother’s eyebrow tweezers. i refused to give them up, said i am a white woman traveling with an american passport, do you think i plan to stab the pilot with a pair of tweezers? they stood with stern faces of pakistani freedom fighters, pointing to the airport-issued lethal weapons chart. i tried my best girlish giggle – these are the only tweezers that don’t hurt; a crowd of barefoot passengers behind me, complaining. just when i thought forget the stupid tweezers, i saw the boxes of confiscated tubes of toothpaste, nail files and pocket scissors, i remembered my grandmother in the sunlight of her coney island bedroom with a magnifying glass, plucking her eyebrows into a thin slightly surprised line. in this graveyard of utensils, three months after her funeral, i cried my first real tears of grief; a tired sikh security director put the tweezers back into my bag, motioned to the others to let the crazy lady through

Marina Rubin lives in New York, New York. Her writing has appeared in such publications as Asheville Poetry Review, Poet Lore, Urban Spaghetti, and The Amherst Review.

Walter Bargen

THE JINGLES

Some claim to hear little brass bells

shaking loose thin vertical slopes

of air. They see a match, protected

by cupped hands, struck

on a distant ridge on a windy night.

It’s all the guidance they need

when the time comes, if there is

time at all, and not just winter’s white

cracking across endless fields.

If time can’t be separated from caring,

it will be dragged kicking

out of the drugstore, thrown

into the back seat of an old Ford,

face rubbed in the snow,

hair cut in rough handfuls,

pants torn on the back fence,

running away. When the time comes

a widow jumps between flat gray stones

in the military cemetery. She lays

a prisoner-made blanket over

a soldier’s fading wars and still keeps

her shoes out of the mud. Rash rain

carries away others’ newly turned earth.

When the time comes, seated

by the bed as a machine

methodically measures and pumps

a seamless ocean, a shriveled arm floats

away wrapped in tubes as evening

clings to the sooted, pigeon-tracked sill

of the painted-shut fifth floor window

where the last rings of light peal.

Teodoru Badiu

Teodoru Badiu is a Freelance Artist and Creative Media Designer based in Vienna, Austria. His work has appeared in magazines, websites and books such as Computer Arts, New Masters of Photoshop: Volume 2, and PSD Magazine.

Walter Bargen

WINGED LIFE

Breathless altitude, touch of vertigo above visions

of cirrus and cumulus, the metal wing

an acute angle with the horizon, a triangulation,

its center an aquamarine afterglow.

Another world, longing for tales

of those who return alien and astonished.

My father’s fluid-choked lungs succumb

for a third time this day to what his body

could no longer resist, a sinking flight

beyond a hospital bed. From the fourth story

window, reading another chapter to the tops of trees

feathering with evening light as across the highway

above the bloody bracelets of braking rush hour traffic,

the hurry and wait the weight we carry

up steep slopes of darkening five o’clock skies.

In the doorway, the nurse waits, wanting to know.

I bend over his shriveled body that hadn’t responded

in days, and more slowly than a distant plane plummeting

seven miles back to earth, he moved his head once

side to side. The nurse left the room as I held his hand,

and after the final release, his hand back at his side,

I turned away and was again looking down at Wyoming,

at Idaho, at Washington, perched on the edge of night.

Walter Bargen has published thirteen books of poetry and two chapbooks of poetry. His poems have recently appeared in the Beloit Poetry Journal, Poetry East, River Styx, Seattle Review, and New Letters. In 2008, he was appointed to be the first poet laureate of Missouri. He lives in Ashland, Missouri.

Tim Kahl

DELIVERY

Half the gray sky has burned off, the delivery

trucks begin to gather at the stoplights.

The drivers on espresso, their work shoes on

the gas pedal, comfortable. The morning

is shaping up like a long line of customers

who expect to get some service for their money.

Another ordinary day at the marathon with

paper napkins on the passenger’s seat for company.

Eyes read the vehicle in front, the mind juggling

the license plate numbers, every car a possible

lotto winner. The fast pass on the left. The slow

keep moving, maybe wave to someone they don’t

know, but this could be dangerous unless it

already happened once before in a movie.

Maybe the car by the side of the road isn’t

really stranded, just somebody who thinks

the road signs are the scenery and got out to

take a picture. Maybe throwing a penny

out the window is really a divination. If it

lands on a guardrail or gravel, the future will

differ. If it bounces, this is how many

strangers will try to keep pace with you.

Suddenly, the day which was way out in front

has slipped behind. It is the drive home and minds

are numbing unless it is summer, Friday, four o’ clock.

Then, everybody is going somewhere, taking items

with them—delivery as a state of being ready.

Eventually the weekend will arrive

and the truckers will no longer belong to each other.

No revving engines. No signatures gathered.

No routes rehearsed over and over.

But the highway will have burrowed itself

into the memory of those who drive for a living,

who drive to be delivered into a blank future

where half the gray sky has escaped its purpose

and the other half presses on like a sermon.

LEBENSRAUM IN THE WILD WEST

for Stephen Cook

A man in a tan Chevy displays

a house flyer in his passenger side window.

Does he really think I’ll call him about

a real estate deal while I’m driving 70 MPH?

Is there an attic? Hey, what’s the

square footage of the garage?

He thinks I’m as desperate to find a house where

I can store my crap as he is to move his inventory.

Four houses on my street up for sale too,

prices softening. It’s like the last two months

the Comanches have been picking off my neighbors,

and I’m the stubborn homesteader on the frontier,

keeping vigil until some mortgage brokers turn up

dead in the streets. I think the banks

should retrieve the bodies, but they can’t even

cut the grass for the two-story on the corner.

I watch the lawn turn brown, rip out

the thistles growing up through the grevillea,

throw the clippings on the piled-up trash.

I want to know if I can give my invoice

to the repo man who comes for your car

in the night. So come on over and drive me

to the last row of houses going up on

the edge of town. There I think I hear the sound

of California’s hide cracking. And yes, yes,

I admit I can’t stop the thrill of fitting

the profile of buyer, buyer, buyer.

Everywhere everything’s for sale

along the highway. I can feel the man

in the tan Chevy coming for the soul

I’ve buried deep in my wallet.

He’s coming to give me the deal of my life,

but I can’t hand my life over to him.

Pieces of it are still on loan from

a movie I once saw about the West.

Tim Kahl lives in Elk Grove, California. His work has appeared in such publications as Berkeley Poetry Review, Prairie Schooner, Indiana Review, South Dakota Quarterly,

and The Texas Review. He is the author of Possessing Yourself (Word Tech Press, 2009). He grew up in Massillon, Ohio.

Gabriel A. Levicky

Gabriel A. Levicky is a writer and artist who is originally from the former Czechoslovakia. He calls his collage work “gablevages.” He lives in New York, New York.

J. Bradley

THE BROKEN CONDOM ON CAREER DAY

Half of you here should thank me

for your parents’ irresponsibility,

the vigor and haplessness it took

to conceive you. To call you all

“accidents” would be cruel.

It’s grueling to shoulder blame

like a crucifix, whirl mistakes

out of torn latex and errant

spermatozoa, be a barrel of fish

for pointing fingers.

When this happens, I crochet

linger into baby booties, cloth

rosaries, moral compass cozies,

the forearms of foster parents;

it doesn’t have to be this way.

Tie off your lust with God.

Call your hands “Bathsheba”,

his mouth a safe word.

Her cleavage heaves like

a collapsing mineshaft

if you ask nicely. May

I never visit your doorstep

like a clumsy knife salesman;

I will only sell you rust

and wounds.

J. Bradley lives in Orlando, Florida. His work has appeared in such publications as Kill Author, Danse Macabre, Lung Poetry Journal, and PANK Magazine.

Leonard Kress

THE JOYS OF MEDIEVAL SEX

It is the 12th century and you just got married.

She is your beloved, and this is your wedding night.

Everyone’s full of advice—is she menstruating?

Yes, stop it’s a sin. Is she pregnant? Yes, stop a sin.

Is it Lent? Yes, stop it’s a sin. Is it Easter week?

Yes, a sin. Is it a feast day? Yes, stop it’s a sin.

Is it Sunday? Yes, stop it’s a sin. Is it Friday?

Yes, it’s a sin. Is it Saturday? Yes, stop a sin.

Is it daylight? Yes, stop, it’s a sin. Are you naked?

Yes, a sin. Do you want children? No, stop a sin.

And no fondling, no lewd kisses, no oral sex, and

no strange positions. Do it only once, and try not

to enjoy it. And make sure that you wash afterwards.

THE COAST OF MAINE

That night we stepped outside into the northern lights–

Pulsating, spiraling web of shimmer, which should have

been the experience of a lifetime, but wasn’t,

because earlier that day we’d sprung loose down the side

of a blackberry barren, shuttled past some beavers

constructing their damn, then—panting–mounted a hillock

overlooking Belfast and Camden and the cuspate

inlets of the Atlantic with our new married friends,

a guilt-riddled playwright and his voodoo-initiate

painter wife, who screamed her night-terrors into our sleep,

while he hugged her to reassurance and jotted down

her fears and nightmares in a pocket spiral notebook

that became the gist of his plays after they split up.

Leonard Kress teaches religion and philosophy at Owens College in northwest Ohio. His work has appeared in such publications as Massachusetts Review, Iowa Review,

Crab Orchard Review, and Missouri Review. He lives in Perrysburg, Ohio.

Kyle Hemmings

YOU’RE ONLY PRETTY IN THE MORNING

Hey mr. pretty boy, she says under

the caress of the hotel’s lemon-scented

downy-softened sheets, I have to go

to work. Last night, she told me

her name was Olga and between us

is a river, a volga of faces we

could have loved if only we had

tried harder or looked a little closer.

The fingers of her hands are snaking armies

holding my lower flank in check,

her knuckles hard as doorknobs

and beyond those doors I can hear

the march of soldiers crippled

by an early spring, deceived by

an early morning glory. March

or die, shouts a dystopian dictator

perhaps my faith or hers in question.

It’s going to be a deadly winter for Napoleon,

Moscow a white ambush, the long trek home,

without prisoners, the memory of bayonets

piercing starving ghosts.

Flicking the remote, she loves watching

reruns of Green Acres in Mountain time,

loves the funny little accents.

I reach for a pack of Parliments,

which never last beyond five wishful puffs.

When will I see you again,

I say in a wisp of surrender.

My erection hard as a chess piece,

my knight wishing to overtake her queen,

as she rises from the bed, naked and elusive

as a messenger pigeon gone astray.

She’s smoking one of my Parliments

saying how she hates the filters.

Standing at the window she’s exposing

her rear guard which could be a deception.

She turns, smiles, slips into the bed.

Ask no questions, she says without words,

my mercenary heart so sloppy in retreat.

TUSK

The sky hangs over you in an endless tusk

ivory is being traded at five cents per share

a real bargain in a bull market

while your wife moans that she can no longer

play Chopsticks at the piano keys

except when you both make love absent-mindedly,

which means you silently call each other

different names in the afterglow

that‘s hard as dentin.

Your children are becoming more unrecognizable,

day by day, growing sideways and distracted,

the way you wished never to grow,

their words dissolving into a mist

that never quite leaves the living room,

furniture reminding you of bare trees,

giant teeth of marked narwhal.

You think: Somebody once lived there or here,

Central Africa or the suburb,

the prairie she wears on her white lily face.

While back at the office,

the boss’s secretary

with an aperitif of excuses for lateness,

your mistress with the loose tooth

and inadequate dental coverage,

on a first name basis with all the spineless Toms,

and hairless aquaphobics,

will look to even the score.

At home, your wife hints again about an oasis

an early retirement abroad,

but you’re more concerned about

your faint heartbeat, its growing irregularity,

a dysrhythmia you conceal from strangers

with white helmets and white spongy lies.

The best you can hope for

is to spring yourself from this life

that is quicksand and slow death,

you, wedged to your elbows,

struggling in blind, delirious backstrokes

like in the hooker‘s bed last night

where you swam

through un-demarcated rain forests

performing amazing feats of mammalian stamina;

tagua is for lovers of natural substitutes

isn’t that what she said?

You’ll tell your wife all about her someday:

her tattoos and her perfect teeth

and your favorite proverbial position,

when the time is ripe,

when the parachutes fail to open,

when it rains elephants from the sky

a trader’s run on pure ivory.

Kyle Hemmings lives and works in New Jersey. His work has appeared in such publications as Bent Pin Quarterly, Literary Tonic, Breadcrumb Sins and Why Vandalism?

John Moore Williams

John Moore Williams is a visual and verbal poet who has published in numerous journals and several anthologies. He is the author of three chapbooks of lexical poetry and was one third of the trio that created [+!] a full-length collection of words and imagery from Calliope Nerve. He lives in Oakland, California.

Mary E. Weems

WORRY

He looks for a job everyday

even Sundays. At first always

alone in the kitchen cause he beats

me out the bed in the morning

cooks our daughter’s breakfast, then ours,

washes the dishes, wanting me to know.

I try to be with him without making myself

obvious, quiet as a shadow, the shame he feels

for reasons I can’t understand leans

in the room like a weight.

It’s been six months and each visit to the unemployment

office takes longer. I don’t ask where he

was when he walks in sober after midnight,

he does not stop me each morning when I get

dressed to go out to earn a living I don’t feel.

BLOW

I used to think Lena Horne

wished she was white.

Not because she was light,

because I couldn’t figure out why

she was in all these movies

not being a maid, not being

poor, not being the latest version

of Aunt Jemima, because all the women

in my family didn’t live like her, and a few

of them were just as bright, because

Lena Horne talked like a white woman

on television, kept the southern

drawl she could switch to quiet as its kept

for when she was not in public.

I heard Lena Horne say once that she married

a white man because he could give her the kind of life

a Colored man couldn’t–I keep remembering that.

Mary E. Weems teaches in the English and Education departments at John Carroll University. Her work has appeared in such publications as An Anthology of African

American Poetry, Pearl Magazine, African American Review, and Obsidian. She lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

Jason Floyd Williams

termites of conversation.

My ol man was telling me

about Yankee’s bar having

the “Girls Gone Wild “ van

parked out front, & how

there weren’t any bare tits

or naked chicks going nuts.

No one was having any luck

except one fellow, an AA biker

named Pig—an ogre-ish motorcycle

trash villain from whatever dime-store,

Fabio-covered, romantic Fantasy novel—

had the Midas touch in spanking

women or getting spanked.

Pig was a good student, though, I’m told.

I told the ol man that

the idea of manufacturing

girls to go crazy seemed

artificial—like a zoo.

It’s a Zen thing, I said.

You never know when it’ll happen.

I had more to say.

I wanted to bring up grizzly bears

& compare them to girls organically

losing their panties, but there was

a freight-train derailment

in subject matter.

My dad started, immediately, talking

about running the tar kettles years back

& taking half-a-dozen Darvons a day

because of the smell.

This led, naturally, to

the pharmaceutical cost of Darvon,

& the prices of other pills

he was taking.

Then insurance. Then politics.

Then his wife losing her job.

Then the sister-in-law living

w/ them, trying to get work.

Then the stepson getting

a disillusionment from his wife.

I mentioned, during a crevice

in the talk, that I had an asthma

attack the other day.

“Maybe it was the mold or mildew

from the abandoned diner next

to our new store, or the termites

still in the floor, but I—“

As if the mention of termites

was the stopped Rolodex reminder

for him—a frayed bookmark holding

the spot in the cerebral catalog, waiting

to be remembered—to tell this story:

“Back when you were a baby,

before the Perrysville place, we

looked at a house with new wood

butted against the walls.

Granddad says, ‘Bob, this place

has termites. Leave it alone.’

So we went to the other houses…”

The story lasted years.

Jason Floyd Williams lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. His poetry has appeared in such publications as My Favorite Bullet, The City, Nerve Cowboy, Cherry Bleeds, and Opium 2.0.

Richard Garcia

POSTCARD FROM PINK

You would like Lily. She wears a wig of straight, coal-black hair. She

has three wig-mannequins on her dresser. Each is wearing a version

of the same wig. There are light bulbs edging her mirror. It is hard to

tell how old she is. She must have been a stripper way back when.

She wears white pedal-pushers. She has a great body. Her

bedroom is done in pink and white. Her Lhasa Apso wears a pink

collar. I am only here because I am painting her bathroom. Pink.

She chews bubblegum but does not make bubbles. I imagine she

has a benefactor. I imagine she has a boyfriend. He is a private

detective. A former Secret Service man. He was one of the men

who were supposed to protect President Kennedy. But the night

before the assassination all the Secret Service men partied hard. He

was hungover the next day and had his eyes closed behind his dark

glasses when the shooting started. Lily ignores me. And why not. I

am not a provider or a protector. I am but the applicator of pink. I

am writing to you from inside a conch shell. The sound of the paint

roller against the wall of the shell is a single note of pink. When I

close my eyes I hear the ocean. Sunset, pink sky. Pink froth of waves.

Papal pink. Pink smoke. Pink mist. Sniper pink.

FALLING PATTERN

Thoughts are falling,

intergalactic thoughts,

falling through the roof

into our bodies.

They don’t make noise

so we think they are

our own thoughts.

They stand inside our bodies

and borrow our vision,

peering out of our eyes.

That is the only way

they can see what we call

the world. They are intrigued

since they know nothing of time

or happenstance.

Katherine, I say to you

although your name is Linda,

What are you thinking?

Nothing you say

because right now a thought

is inside you

peering out of the amber

kaleidoscope of your eyes.

Katherine of the steppes,

of the plateau rising out of

a jungle where no man

has set foot. Katherine

who says we are floating.

We’re falling I say,

falling in a pattern

just like the dust motes,

some of which

are extra-terrestrial,

really, suspended,

spiraling down

invisible stairways

of light.

Richard Garcia lives on James Island, South Carolina. His poetry has appeared in such publications as Ploughshares, Colorado Review, Cortland Review, Blackbird, and Notre Dame Review. His collections of poetry include Chickenhead, The Persistence of Objects, Rancho Notorious, and The Flying Garcias.

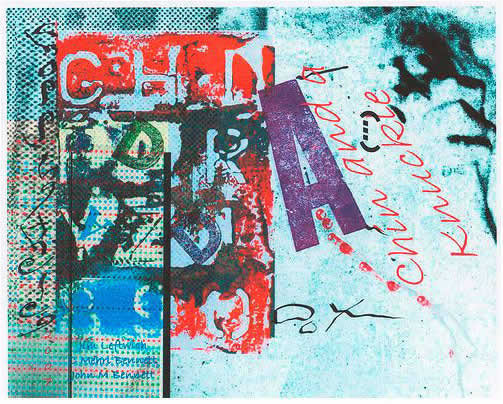

David-Baptiste Chirot

David-Baptiste Chirot lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His work has been published extensively. This image is from a series entitled “No Accident.”

Richard Stevenson

“LOW PRIORITY”

Because she lives in Surrey

in a low-rent motel;

because both her parents

are currently unemployed;

because she’s a tom boy

and talks to strangers,

including men in the motel;

because she’s precocious

for a twelve-year old.

Because she has already been

busted for shoplifting;

because she didn’t return

her friend’s shiny new ten-speed

when she said she would;

because she didn’t turn

up for school the very next day;

because she was customarily

foot loose and fancy free …

Because Mr. Walker isn’t

a blood relative and can’t

file a missing persons report;

because her parents hadn’t either,

assuming she was staying

with her friend Clive Walker

who had lent her the bike

so she wouldn’t be late for dinner …

Never mind that Mr. Walker

knows she’s not staying with them;

never mind that it’s been a week;

never mind that a known

sex offender lived in the neighbourhood,

that Clive’s bike was eventually found

abandoned behind the neighbourhood Vet’s,

that it was parked without a scratch;

never mind that Clifford Olson’s

apartment was right across the street;

never mind that he was a perpetual liar;

never mind that Child Welfare

office officials stood corrected

when they said she was in a foster home.

The kid roams. The kid wants

to keep out of her father’s face

and not get under foot in the

Weller’s cramped motel room.

Her father was angry a lot

of the time, but “forgot”

to call in the missing person’s

report. She probably just took off –

and, besides, reports of her squatting

in a refuse pit behind a burger joint

didn’t check out. She’ll turn up

when she’s hungry and contrite

and has no more piss and vinegar

in her. Trust us: she’s just a runaway.

A runaway with eighteen stab wounds

tossed like refuse on waste ground

next to the dike in Richmond,

the fancy, high-rent municipality

next door. She’s just the girl next door.

There are hundreds like her who

disappear every day. Most of them

are runaways. Most know better

than to get in cars with strangers.

Most of them turn up eventually.

We’re sorry to have to tell you

that your daughter has been found

by a jogger. We’re sure it’s her this time.

Richard Stevenson has read to audiences across Canada and is the author of 23 full-length books and 7 chapbooks, including, most recently, Hot Flashes: Maiduguri Haiku, Senru, and Tanka, Parrot With Tourette’s, A Charm of Finches, and Wiser Pills. He also occasionally performs with the rock/poetry group Sasquatch. He regularly reviews poetry and fiction, and periodically runs adult and young adult workshops. He holds degrees in English and Creative Writing from The University of Victoria and University of British Columbia and teaches Canadian Literature, Creative Writing, Children’s Literature, and Business Communication at Lethbridge College in southern Alberta, Canada.

Ed Pavlic

“IN HIS HANDS AN INVISIBLE OBJECT” : STENOGRAPHER’S ERROR: ANONYMOUS TESTIMONY REMEMBERED BY EVERYONE HOWEVER NONE RECALL HAVING HEARD OR FROM WHOM OR WHEN

said : if these hardly heavy gray hands happen here again well that’d prove he stood up stone on stair-steps above how hi & alone over steel fortresses held upside down winds caught in icicles off the edge of the bright-bald slaughterer’s roof forget tousled hair at union scale three months or thirty years in & out thru Tintoretto & Giotto : mutiny on the Sahara dune of a cheek bone : a thousand sittings & “I’ve never

seen you before” he lied about the inside & how hard he loved to rage to himself he lied about a world that insists on hands as if fingers fit thru liquid he lied about the color of the fortress & denied he knew the temperature that changes wind to ice lied about the color

of blood frozen into steel

Exhibit A : he brought a charcoal sketch contempt to the oath swore to the fact that a fact darkens like clear water under its own weight said : go on & call it pressure & that shadows of liquid displace nothing therefore sink thru us all & slip forth without

the rotten ties of motion seams swore : if it’s seams that

move you then swear an oath to such as you’ll find if not look away from death-scars on these hands under my liquid hands how could they happen? again & again here in the violence now in front of us all that leaves no trail an event of absolutely no rhythm a trace therefore impossible to elude her wet face an object perfectly without attribute a steel beam holds the bloom of smoke & a dance explodes room to room

seamless as an ace dropped on the wood the way our shadows sharpened

themselves & knelt down to pearls as if we never cut whispers

in rooms above other rooms

Ed Pavlic is professor of English and director of the MFA/PhD program in Creative Writing at the University of Georgia. His poetry has appeared in such publications as Indiana Review, Agni, The Cortland Review, Ploughshares, and Jubilat. His latest books of poems are Winners Yet to be Announced: A Song for Donny Hathaway and …but here are small clear refractions. His book Paraph of Bone & Other Kinds of Blue, won the American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize. He lives in Athens, Georgia.

John M. Bennett / C. Mehrl Bennett / Jim Leftwich

John M. Bennett is a poet and artist who has been published widely. He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

C. Mehrl Bennett is an artist and poet. Many of her images are imbedded with text. She often creates her art in collaboration with other artists.

Jim Leftwich has collaborated with many writers and artists. He lives in Roanoke, Virginia.

Tim Hawkins

TASK FORCE

I am taken aback that so many seem

to become so energized by this process

of producing a plan to produce a plan

that has less and less to do with trees and concrete

and more and more to do with a fractured agenda

and the sound of words strung together

by the force of the human voice, so unlike

the sound of poetry or even prose.

I would suggest that some are still running

for class president of the seventh grade

if I wasn’t so busy hanging out

by the water fountain looking cool,

and scribbling these marginal notes.

I will concede that there is plenty of direction

in this document, and there are more

than a few data. However, given

the absence of consensus, I would motion

that we adjourn from this sound-proof room

out into the bright afternoon, to get ourselves

back on track, to commit some tasks, with force,

the way a child might envision our mandate.

We might also just clasp hands in silence

in a huddled mass on the carpeted floor

to escape this maelstrom of discourse

devoid of perspective, context and common sense,

to remember the way things were before we came in here,

and the way things are outside so many rooms.

Or, barring these unlikely eventualities,

might I suggest, that we make certain, at the very least

to peruse the support materials, these

lovely, leather-clad briefing books

that someone has so kindly assembled for our edification,

before next week’s penultimate session.

Tim Hawkins lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His work has appeared in such publications as The Literary Bohemian, Umbrella: A Journal of Poetry and Kindred Prose, Blue Print Review, and Underground Voices.

R.T. Castleberry

SEE ME LATER

I’m cell phone mad, passively mobile–

less interested in methods of consecration

than my neighborhood brothel, Methodist devotionals,

discourtesies of creditors and the alcoholic dead.

I wake to music,

talking bootlegs and Alabama boogie,

Sam Cooke’s church recordings,

Van Morrison’s TB Sheets.

I have a hundred haiku memorized,

57 songs in B flat.

I circulate 3 lines of chatter–

salesman, cynic or stooge.

I manage the major holidays–

Christmas cognac, Easter chocolate,

the slaying of a lamb for Leonard Cohen’s birthday.

There’s a suicide guess at every luncheon,

winter country ruins passed in an open touring car.

Sharecroppers starve on the move.

Railroad ties are soaked and smoking in kerosene clouds.

I’m sick, a little dizzy.

New medications float through my chest,

cause my head to fall into my hands,

cradle senseless on the reading table.

I hear a busker with a 12 string

snatching at “Tin Cross Blues.”

This is how I manage my distractions:

the darker seasons drain me

and it’s convenient not to care.

R.T. Castleberry lives in Houston, Texas. His work has appeared in such publications as Paterson Literary Review, Silk Road, Comstock Review, and Argestes.

13 Miles from Cleveland

Edited by Joe Balaz

Joe Balaz lives in Northeast Ohio in the Greater Cleveland area. He edited Ramrod–A Literary and Art Journal of Hawai’i, and was also the editor of Ho’omanoa: An Anthology of Contemporary Hawaiian Literature.

All works appearing in 13 Miles from Cleveland are the sole property of their respective authors and artists, and may not be reproduced in any way or form without their permission. © 2009