Volume 3, Number 1 2010

Kyle Hemmings

LAST CHANCE FOR HAPPINESS

Van Gogh had an estranged wife.

Kept her a secret even from Theo.

Hid her in his mother’s Chinese vase

of wilting lilies or in a closet of starry nights.

Pressed his ear to the door

and heard post-impressions of love. She cooed.

He answered. She said make me real

from a distance. He said up close I am so needy

and I need a good shave

with a steady hand. Listen, she said. And he

heard the ocean, the wistful rustlings

of his childhood near wheatfields

and ruined corn. She grew silent. He smiled

and listened with his good ear.

He never gave up hope until he opened

the door and heard her speak with his

own words from last night’s dream. He impregnated her

with seashells and the ocean rose and swirled

bore him demon children in gun metal gray.

LAST CALL

In the street, the drunks mock Last Call,

dirty dance against meager traffic

then return to their lives of constant hangover

and mid-morning skeletons. I turn to my new

lover, a girl with perfect teeth and razors

in her eyes. She says she knows an after-hours

spot where we can grow numb and never sober.

Baby, I say I only got a bad heart and loose change,

just enough for one song about broken wings

and stretched-too-thin lies. It’ll do she says.

She’s a cheap date but a costly lay.

In the bed of night where there’s a constant

turnover of housekeepers, she’ll say she wants more

but I’ve already disappeared into the

Hobroken of middle-age stamina,

irregular bus schedules.

On my tomb it will read:

They only accept exact change.

Peter Ciccariello

Peter Ciccariello is an artist, poet, and photographer. His work has appeared in such places as MOCA The Museum of Computer Art, Oregon Literary Review,

The Long Island Quarterly, and Otoliths. His book Imaginal Landscapes, an experiment with the poem in landscape as it relates to poetic geography was published by Xexoxial Editions. He lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

Kyle Hemmings

THE LAST DAY

On my last day in vivo, I treated myself to a banana split

with walnut topping at the Kool Queen, then, bought three pizzas

with sausage and pepperoni and lemon meringue pie at the A&P.

I bought a carton of cigarettes at the deli on Haymarket, shot the breeze

with the Indian owner whose smile always betrayed the wide gap

between the front teeth, and paid for the cigarettes with a hundred

dollar bill. I was feeling flighty and disingenuous. Perhaps like

Holly Go Lightly if she were a man. After all, today I was going to die.

When I returned to my apartment, I sat on the couch, me-so short

of breath from the walk. I didn’t rearrange anything, nothing to pack

or unpack. Rather than thinking of all that I could have done better,

all my losses and miscalculations, I took stock of all that I enjoyed—

crimson sunsets, the fine curves of a young girl, the morning mist

at Edgewater Park. Was it enough to miss this world? To sustain me?

I couldn’t conclude anything. I had lived most of my life skirting

the perimeters rather than being engaged. Much like a bulging-eyed

Beagle on a leash. He wants so much, but his reach is too short.

Before everything turned completely black, my trapped-in-a-closet self

stepped out. My perspective shifted. I now watched my body lean forward,

crumble to the floor, the arms and neck so slack.

I thought if there is a heaven, it’s where I always thought it was:

The Crazy Diamond Tavern, where I’d corral with the old guys,

the janitors and schoolteachers, the hustlers and the hustled.

The bartender on the day shift was always God the Father

and Jesus worked the second shift. Happy Hour would last an eternity.

I will walk in and bathe in the aromas of cigarette smoke,

unwashed flesh, a woman’s cheap perfume that she calls

rosewater, but another would call putrid orchid.

I will imagine the taste of flat beer, but no one will ever

defy God the Father, the master of pouring glasses

of half-foam. I will shout out, “Hey, listen up.

You’re all a bunch of useless drunks!”

And the most beautiful thing about entering heaven

is that no one on earth can hear you.

Kyle Hemmings lives and works in New Jersey. His work has appeared in such publications as Ophelia Street, Prick of the Spindle, Rumble, and Silk Ink Press.

Valery Oisteanu

BEAT ANGEL BLUES

TO HAROLD NORSE

The cosmic hustler is now a pure spirit

And so are the masters of the Dream-machine

Norse continues to whisper from the great beyond

Howling, and writing the story of his crazy karma

O! Hollow America! Hollow America

The harder one hits, the deeper the sound

In the passage underground

The virtual museum of the Beats

They who have forgotten you so soon

Omission accomplished

Tears drop as red petals off a rose

All roses cry, I wanna die! I wanna die!

There are no degrees of separation

Between him and Ira Cohen

Between him and Leonard Cohen

Between Corso and Norso

His ghost still haunts the island of Hydra

Sex and Marijuana evenings with Zina

Her spirit reincarnated in Harold

Where he performs in the Café Purgatory

For the hip elite of the Generation Beat.

ARSHILE GORKY TALKS WITH JACKSON POLLOCK

Let the black birds fly as miraculous as handwriting

Let the paint fly in the rhythm of Charlie Parker

Working from the heart, painting day and night

Canvases on the floor, canvases on the wall

Surface virtuosity of paint and movement

Rhythm and pause sequencing and destroying

Horizontal murals spinning into chaos

He throws the paint in the rhythm of jazz

He throws the paint with a stick and a brush

Many try to kidnap him

Many try to love him

But Lee Krasner saved him

The she wolf perishes in flames

The totem is the guardian of the secret

The white angel dances into the blue unconscious

Arabesque dream meets troubled queen

These are the titles of Jackson’s work

Peggy Guggenheim tried to seduce him

Siqueiros tried to influence him

Alonso Ossorio and John Graham got drunk with him

But Lee Krasner saved him

Sounds in the grass, vortex full fathom

Out of the Web Echo are his last paintings

Before driving into the eternity

Followed by the Lucifer.

Valery Oisteanu was born in Russia and educated in Romania. He adopted Dada and Surrealism as a philosophy of art and life. His work has appeared in such publications

as Exquisite Corpse, The Pedestal Magazine, Big Bridge, and Evergreen Review. He lives in New York, New York.

Mary Ellen Derwis

Mary Ellen Derwis lives in Brecksville. Ohio. Her work has appeared in such publications as Otoliths, Oregon Literary Review, Bosphorus Art Project Ouarterly, and Unlikely 2.0.

Ruth Foley

KNOWLEDGE

Would-be informer, what will you

tell us now? What knowledge left

your head that night, when you were

forced to kneel behind the Mavis T. Blatchett

Elementary School? Eleven years

your mother waited for her own

knowledge, waded through the flood

of muddy memories and false eyewitnesses:

I saw her buying cigarettes in Abington.

She got her boobs done.

She dances at Cheetah’s on the state line.

Your mother knew you

weren’t perfect. Your mother knew

you weren’t her baby girl.

And soon enough, the crazies

stopped calling the tip line. Soon

enough, your father stopped

slowing down each time he passed a girl

with long brown hair, leaning

in a doorway in Kenmore Square,

a cigarette held in her mouth,

a proposition he couldn’t bear

to contemplate. No parent wants

to think their child can end this way—

knees down in the dirt, maybe

whispering a half-forgotten prayer,

maybe making an offer.

Whatever you saw, it was enough

to take the Family down,

so you went down instead, a stray piece

of cellophane stuck to one crocodile

high-heeled shoe, the other on its side

in the grass behind you. You fell.

The man who took you dropped you

back into the earth face-down

so he wouldn’t have to close your shadowed

eyes against the dirt he lay down

after you. So he wouldn’t have

to touch you again. So he wouldn’t

have to watch you watching him.

And you—your knowledge bleeding

through the spaces between pebbles

and dirt, turning the dust to something

thicker than mud or blood alone,

your favorite pink blouse

rucked halfway up your back—

you didn’t know the difference

and didn’t care by then. And if a child

young enough to be the son

you might have had—if that child

hadn’t missed an easy out fly ball

at recess on a false-spring

November morning, hadn’t found

some bones that looked like

fingers, well. Then we’d know

even less than we do now.

MAN PRETENDING TO FALL OFF BRIDGE ACTUALLY FALLS

AP headline

It’s not as funny as it sounds. One minute you’re flying—

two or three too many Jim Beams—looking over your shoulder

at your new girlfriend, some woman you think

you might love eventually, or maybe not, but she’s good

enough for now. The night is clear and starting to warm,

and your girl’s been warming up all night, putting her hand

on your thigh under the table or pressing against you

when you put your arms around her while she pretends

she doesn’t know how to shoot pool and you

pretend you want to teach her. And last call came up

and you were out of money anyway and the bar

was getting smoky and stale with desperation (but not

you, not the girl, because you’d already sealed

that deal a couple of nights ago, and she’s yours now

until you get bored or mean on liquor or

both) and you stumbled out into that almost-summer

Thursday night and blinked a little at the headlights

in the parking lot and the way the stars

had set themselves to spinning. And you drive

with the windows down to keep yourself awake—

it might not be winter, but it’s still cool enough for that—

your girl with her shoes off, her feet propped

on the dash, her head rolling a little on your shoulder.

And you’re not even halfway home before you have to

take a piss, and the bridge seems good, you can water

the marsh grass with a little spring rain of your own.

Your girl is laughing, and you turn your back,

even though you’ve got nothing she hasn’t seen before

and she’ll see it again later if you’ve got anything to say

about it. You’re flying, I tell you. They don’t make

nights better than this, not where you come from.

And you make some kind of whoa sound, spin your arms

like you’re losing your balance, laugh like

the idiot you are, and that’s all right, that’s fine, she’s

laughing, too, she hasn’t stopped laughing, but you look

over your shoulder to catch her eyes, to see her throw

her head back, to make sure she knows how funny

you are, and then you’re really flying, the night falling

away as you rush towards the reeds and you don’t even have

time to think about it all until later. In the moment,

it’s all piss and air and a laugh turned into some kind of gasp

you’ve never even heard before, and a cry comes

to your ears, a cry like a hunted animal or a lost child,

and it’s a moment before you realize it’s you,

you’re howling into the wind your falling makes.

And when you wake—and you do wake—the girl

is gone, because, she says, she wants a man

with half an ounce of common sense, but you know

what she means is that she wants a man who’s whole,

who can feel his feet against the ground, whose thigh

she is unafraid to touch. She wants a man who can make

her promises, even if he has no plans to keep them.

Ruth Foley lives in Attleboro, Massachusetts. She teaches English at Wheaton College. Her work has appeared in such publications as River Styx, Oxford Magazine,

The Comstock Review, and Confrontation. She is the Associate Poetry Editor for Cider Press Review.

Larry Smith

TU FU ENTERS THE CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY

They didn’t need me today,

said Old Ed could handle things—

few customers, but I know too

it’s to keep me from full-time

and collecting benefits.

Yet they wait till I show up,

so I stand here in early light

waiting for Bus 10 to take me home.

An old woman standing near

looks over at me and speaks,

“I clean for people out in Shaker.

How about you?” She’s dressed warm

in what they call a Pea coat,

her brass buttons shining in street light.

“I do dishes at Ming’s, but

today they don’t need me,” I shrug;

she nods, knowing the way it is.

I stare out across Superior as

lights come on in the long gray building.

“That’s our library,” she says,

and her words hang in the air

as a gush of traffic passes.

I stare at the grand doors,

then find myself crossing,

climbing the broad stone steps.

I enter the quiet space

passing under the watchful eyes

of a blue uniformed guard,

and into a huge dome,

arches over every door and window.

I carry nothing to check,

only my pocket notebook

where I scribble my poems.

A woman in a blue suit smiles.

“You’re our first customer today,”

she says. “May I direct you?”

And I think to say: “Literature—Chinese.”

“That would be our second floor,

up that stairway.” I bow slightly

and walk to the marbled steps,

a huge painting spread before me.

In such space and richness

I feel both large and small.

I climb, then enter an archway

to a room as wide as a field.

Lost among shelves of books,

always my friends and guides,

I am stranger again in a city of words.

I pass the dim blue light

of computer screens, finding my way

down marked streets of bookshelves

till I come to “PJ”—my poetry homeplace.

My hand skims the textured wall

of books of varied colors.

I smell the glue of aged pages.

and would choose them all—

devour them there among the stacks.

The world dissolves outside the windows.

On a stool I feed for hours

take down old Lao Tzu…

As darkness lightens,

murky comes clear,

and stillness moves.

At noon I take out my pen.

Larry Smith is a novelist, poet, reviewer and editor. He directs Bottom Dog Press. Recent work has appeared in McGuffin, and The Cortland Review. He lives in

Huron, Ohio, along the shores of Lake Erie.

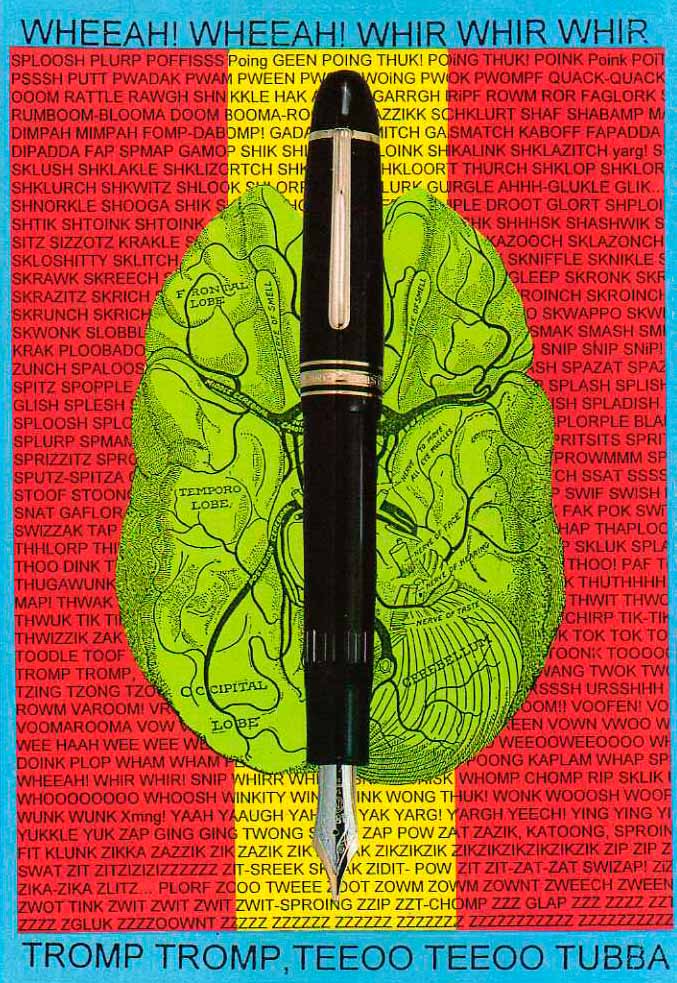

Carol Stetser

Carol Stetser is a visual poet living in Sedona, Arizona. Her work has appeared in such publications as Vispoeologee and Rampike. This print is part of the collection

Mad Comix using words by Mad Magazine cartoonist, Don Martin.

Tim Kahl

SCRIPT OHIO

Oh, you ore boats from over in Lorain,

awakening the question of beyond in the lake.

The mills of Cleveland and their Youngstown brothers

leap to make the steel rails and trestles.

The jagged lines of cement tossed across

the cathedrals of wheat and soybeans etch

a cursive glyph into the earth. The tired flow of blood

through the canals climbs the tiers of the heartland,

the old towpaths running alongside like

shadows accenting italics. Yet where did

the interurbans go that ran between Dayton

and Cincinnati. They went the way of wagon ruts

pressed into Zane’s Trace, the way of passengers

on steamers charging up the river.

The aromas of the eras start to mark the plains

with destinations. The paths expand,

and the grass is trampled into waysides.

There the travelers stop to see what the cloud seed

will rain down in the future. The rivulets

inscribe the name of the state in the clay;

the turnpike throws off new asphalt shoots,

every tendril a letter. And the band plays on,

blaring Across The Field, championing its

victories. The o’s circuit is complete.

The dot on the i is where you are now.

THE WESTERN RESERVE

Cuyahoga fever thinned the ranks of the surveyors

whose lines squared the interests of men in

Connecticut. Their maps were made from sideways

glances at the stars. Then came the settlers to gash

the first fields after columns of smoke were erected

and slowly evolved into air. Their frontier sons

were born with an ax in one hand and a gun in

the other, growing up through a tangle of trunks and

broken branches. They split rails for fences around gardens.

They believed the hearts of Carolina parakeets by

the stream were poison, and all jays went to

hell on Fridays. But the cardinals should nest near

the door of the cabin, and these were not meant for

hunting. They believed the hickory was a sign of

fertile soil. Flax seed grew well on burial mounds,

and flint could be found while digging up potatoes.

There was more and more sky to believe in,

more room in the landscape for liberty to be

debated. But as the market for wheat developed,

the argument increasingly grew one-sided.

The cradle scythes left a stand of stubble, and

the swamps were drained. The hogs devoured

copperheads with a flourish. The state seal featured

a canal barge moving past a field. All roads led to

the millers who were clearing their waterwheels of

driftwood. The rivers kept pushing the fallen bits further,

murmuring to the uninitiated back at the source of

the trade route in New England, Go west, young man, to Ohio.

More came and saw an empty place against

the Cuyahoga sky that they could have faith in.

At night the stars were clearly visible. The land was hope,

and the rest of the time their prayers kept them busy.

Tim Kahl lives in Elk Grove, California. His work has appeared in such publications as Berkeley Poetry Review, Prairie Schooner, Indiana Review, South Dakota Quarterly,

and The Texas Review. He is the author of Possessing Yourself (Word Tech Press, 2009). He grew up in Massillon, Ohio.

Martin Ott

REQUIEM FOR PLUTO

A small black orb is watching you

untraceable by the human eye.

Sometimes you feel there is a pinhole

boring through the sloping neck top,

exposing the frontal lobe to scrutiny.

You imagine the all-seeing gaze

of a dark-star deity guiding you.

You look for it from your favorite

coffee shop, staring at the same

street corner for a woman’s dress

to rise, drawn by gravity that should

not be. The day you saw him appear

through the bottom of your water

glass no one believed you found

the God of the Underworld strolling

your neighborhood but you had faith

in the power of things unseen.

Your waitress listens to your dreams

and dots your check with a circle.

You imagine a smiling face there

waiting to be eternally discovered.

Martin Ott is a freelance writer and a graduate of the Master of Professional Writing Program at the University of Southern California. His poetry and fiction have

appeared in such publications as Poetry East, Tampa Review, New Plains Review, The Literary Bohemian, and Valparaiso Poetry Review. He lives in Los Angeles, California.

Mara Patricia Hernandez

Mara Patricia Hernandez was born and raised in Guadalajara, Mexico. Her work has appeared in Other Cl/utter, Otoliths, The New Post-literate: A Gallery of Asemic Writing, and Noncessence: A Journal of Nevercheology. She lives in the San Francisco Bay area.

Jason Floyd Williams

poor, big-headed Charlie.

The conversation was a tributary, a Kerouac creek,

birthed from a previous chat about

downtown Cleveland & factory jobs.

Seems Janet’s dead sister, Dorothy, had

a handicapped son named Charlie.

“Charlie had a big head, the size of a

summer watermelon. And he was real slow.

Well, folks saw this and took advantage of him.

He was robbed and beaten in Cleveland.

Dorothy brought Janice back to Stringtown

after that.”

“Who’s Janice?” I asked.

“Janice is Charlie. After Dorothy found out

Janice was retarded, she named him Charlie.”

“Who names a boy Janice?

And makes life easier on him after she discovers

he’s handicapped and changes his name?”

“Well, Dorothy had strange names for

all her kids. She read ol, pulp Romance books.

So her last girl was Andy; the oldest girl

was Danny; and the oldest boy was Cindy.”

“Criminy, how many kids, with rotten names,

did she have?” I asked.

“Four kids,” Janet said.

“And many, many abortions.”

“Didn’t they have condoms or

sandwich bags in Stringtown?”

This caused Floyd, seated at my left, to spit

up his sauerkraut.

Seems like he’s recovered from the stroke.

A VidStar epilogue.

For Les & Staff,

Sometimes the victory of David

over Goliath is not so clear-cut.

Goliath may appear dead.

His lifeless body—like hoarded

mounds of lunch-meat—, a stone

beside his giant head (a runaway skin-mole),

& afterwards a crime chalk-line

that’ll keep the kids hop-scotching

for years.

David may feel secure.

He may settle down, get married.

buy a home in the country.

He may even open a video store,

renting out good ol classic films.

This might last awhile—

say 27 yrs.

In each increment of 5 yrs,

David thinks, “Well, it’s been a solid run,

but there’s competition popping up

all over.”

David endures, however.

He sees other ma & pa video stores

come & go, like Dust Bowl travelers.

Years pass.

Some tough & mean years, others

very profitable.

It pays to specialize, David thinks.

It also helps to have a good crew—

Joe, Shannon, Missy, Ed & others,

David reflects.

Part 2.

No one checked Goliath’s pulse, though.

His body disappeared.

His obituary was lost by

the editorial staff.

Goliath sought revenge w/ Ahab’s patience

& Madoff’s cunning—

He planned competition in the forms

of NetFlix (folks won’t even have to leave

their homes or, God forbid, interact

w/ sales clerks);

Red Box (those inflamed skin-tags protruding

through the landscape—again supporting & enabling

the xenophobes among us); the big corporate stores,

The Hollywood Videos, The Blockbusters,

w/ their vast square footage of

new releases & limited old selections

(forget about the grainy ol flics—

Goliath abhorred Bogart & Cagney—

embrace, w/ incestuous arms,

the CGI generation).

Part 3.

We were at my grandparents

the other day.

My grandfather’s drifting out

of this life one pound at a time—

something under the skin, something unknown

in his stomach, something interrupting

his appetite.

He was 175 lbs two months back,

now he’s 142 lbs.

We avoided talking about death

& the afterlife by watching TV.

We could only watch pieces of it—

our dogs would bark; the ol man

would have a coughing fit; someone

would comment about the snow.

The movie was called The Letterbox.

I forget the main character’s name,

but it’s about a dying woman

who has month-long relationships

w/ socially-boring, interpersonally awkward men.

Sara’s her name, now I remember,

(one fellow kept repeating it, while filling

out a crosswords puzzle: his mantra), &

she encouraged Mr. November or Mr. February

or Mr. Whatever-Month, to write sonnets

about her, to water-color

portraits of her.

She’s easy-on-the-eyes & a little goofy,

so all the men quickly do these things.

The psychological portions I gathered

about why Sara did this—

change men like menstrual cycles—

was explained by her neighbor,

some pro-vegetarian, sign-painter:

“She wants to be remembered.

She’s dying and she wants to live

on in memory.”

I guess that’s all we want—

to just be remembered.

Jason Floyd Williams lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. His poetry has appeared in such publications as My Favorite Bullet, The City, Nerve Cowboy, Cherry Bleeds, and

Opium 2.0.

John M. Bennett / C. Mehrl Bennett / Jukka-Pekka Kervinen

John M. Bennett has been published extensively and has exhibited and performed his word art in numerous venues. He is Curator of the Avant Writing Collection at The Ohio State University Libraries. He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

C. Mehrl Bennett is an artist and poet. Many of her images are imbedded with text. She often creates her art in collaboration with other artists. She lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Jukka-Pekka Kervinen is from Finland. His work has appeared in numerous publications.

Timothy Pilgrim

FENCING IN DARKNESS

To begin, a list. One, sword,

pointed, thin. Two, mask

with mesh, dark, tight. Three,

wire, barb strands twisted sharp.

Four, counselor, priest,

confessor, friend. Someone

to deal with tears, excuses,

lift spirits up again.

Five, light, bright,

so nothing hides.

To stay alive, survive,

make backup plans of plans.

Re-read Plath, Frost, Jung.

Recite “Mending Wall” by moon

or in full sun. Know what

must die, let live again.

Learn to stab, feign, sway.

Drive point home in dusk

then in day. Practice blindfolded,

eyes squeezed shut. Dream

at night, knees curled to chin.

Shun mirrors in life;

learn fencing well, others out,

yourself in. Know

if you are suffocating,

or dueling death again.

Timothy Pilgrim is a journalism associate professor at Western Washington University. His work has appeared in such publications as Seattle Review, Quaint Canoe,

The Curious Record, and Bathyspheric Review. He lives in Bellingham, Washington.

Ross Vassilev

UPPER EAST SIDE

I went to a racially mixed

school in New York.

a lot of the black kids

never did their homework

cuz they didn’t want

to be seen as acting white.

the black kids and the

Pakistani kids hated

each other while the Mexican

kids talked to each other

in Spanish and minded their

own business.

I spent most of my time

stepping on caterpillars.

no one told me

they turn into butterflies.

Ross Vassilev was born in Bulgaria. He is the editor of Opium Poetry 2.0. His work has appeared in such publications as Word Riot, My Favorite Bullet, and Strange Road. He lives in Delaware, Ohio.

13 MILES FROM CLEVELAND

Edited by Joe Balaz

Joe Balaz lives in northeast Ohio in the Greater Cleveland area. He edited Ramrod–A Literary and Art Journal of Hawai’i and was also the editor of Ho’omanoa:

An Anthology of Contemporary Hawaiian Literature.

All works appearing in 13 Miles from Cleveland are the sole property of their respective authors and artists and may not be reproduced in any way or form without their permission. © 2010