Volume 4, Number 1 2022

Kathy Smith

Rob Sean Wilson

ANANDA AIR, III

Three uncommonly handsome travelers are flying

In a balloon over Ames, Iowa, a woman

And two men. They can see the snow falling

To the fields below where children look up in

Bundles, with open hands, waving at the machine.

They are making aerial history.

They are making the weather talk to farmers

Who look up at the steaming smoke and applaud.

The arrogant man on the left is named Vincent,

He is the angel behind the project.

The festive, red coated man on the right

Is named George, the maker of the gilded balloon.

Between the two men sits a woman dressed

In white and black gowns, with a cowboy hat on:

Her name is Ananda, Ananda Air.

She looks down on the fields with open arms.

She is waving some flag, maybe the flag

Of a region in India called Panduranga,

Where the poet saints come from

When they are not reborn as trees.

It looks like the flag of England, where she was born.

But she is flying over a new land, has new feelings

Of upward bound tranquility and release.

She looks plaintive, as if the snow means disaster

And change. For her nothing is constant

Except the wind she follows, which blows the balloon

Across the plains of Iowa where cows exalt the grass.

Some rumors call the lady voluptuous, some sagacious,

But she goes on flying above this storm of need.

She takes a nickname for the journey, Sweet Tranquility,

Surprising the men like the early fall of snow.

She is off across the continent: Ananda, Ananda Air.

Kathy Smith

Visceral as a fresh caught cut perch

yearning as the dog looking hours out the window for the car’s return

I love you, I would say to my family

the gulp in my heart tendered between mortar and pestle

like the unexpected swipe of a burnt cigarette on the arm.

With some,

we spend more time together in dream

than real life

expansive surprises of rooms

come out of a flap of shuffling cards

like a rabbit out of a hat

We make a cardboard castle

We sit on the patio and watch the backyard pond

the trees as sweet to sight as

fresh washed salad

I know

the knowledge of what the Cuyahoga

has done to its banks over centuries

The accordion wheeze

the new born spring swallowtail

taking its first steps before us

we only know where it folds up its

wings to rest because we see

where it’s been

where we are now, where we

have been

Let’s hold it, let’s keep it here

Kathy Smith (Lady K) is a writer, poet, web designer and engineer from Cleveland, Ohio. She enjoys nature, listening to books, household and garden projects, and cooking. She is the editor of The City Poetry, a literary and art magazine of Cleveland, http://www.thecitypoetry.com, and more of her work can be found at Walking On Thin Ice, http://www.walkingthinice. She lives in Cleveland, Ohio.

Rob Sean Wilson is a Western Connecticut native who received a doctorate in English

at the University of California at Berkeley, and was the founding editor of the Berkeley Review. He has taught in the English Department at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and Korea University in Seoul, and was a National Science Council visiting professor at National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan. Since 2001, he has worked as professor of American literature, creative writing, and poetics at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He has written multiple books of poetry and cultural criticism, and his poems have appeared in numerous publications. “Ananda Air III” is from When the Nikita Moon Rose, his latest book of poetry.

Steven B. Smith

Joseph Stanton

TO THE HACKERS OF THE HEAVENS

Wielding your keystroke hatchets

you have done the deed and discovered

a drift of white mist and beyond it,

as far as your screen can scan,

a blue sky and a midday sun

too hot to click on.

As your evil algorithms

beat time on celestial storage drums,

your digital screens scrum

angels singing high-keys,

and your hackings find at bottom

cherubim dancing ecstatic

on the heads of memory pins,

chips off old data blocks,

and your hackings reveal at top

seraphim singing to an Absolute Being,

aloof and paring his finger protocols,

whose mystic eyes admit

no thefts of identity,

knowing exactly, as he does,

who you are.

MODERN TIMES

Charlie Chaplin’s best movie

makes a factory,

despite its inhumanity,

a place of precarious liberty,

a stage for prancing oil-can dancing.

All transpires within

a city’s cruel incivility—

this tale of unlikely love

between a tramp and a gamin,

who are, Chaplin declared,

“the only live spirits

in a world of automatons.”

Joseph Stanton is the author of seven books of poetry, the latest which is Prevailing Winds. His poems have appeared in Poetry, Harvard Review, New Letters, Antioch Review, Poetry East, New York Quarterly, and many other journals. He is Professor Emeritus of Art History and American Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Steven B. Smith

We know

thanks to postcards from the end

it’s not destination

it’s the journey

the getting

not the gone

which makes me think

Sisyphus must be one happy dude

blessed by endless doing

never done

always on way up

before failing down

never reaching boardroom

to piss its gold-plated toilet

no kissing ass or playing blind

just rolling rock in endless climb

with time to enjoy view

as failure falls

in sparkle of downward dew

no worry

no warts

except (as always)

hurt for the heart

Smith was born, is living, will die . . .

Poems & art since 1965

he resides in Cleveland, Ohio.

Jim Kraus

IN THE PINEAPPLE FIELD, THINKING ABOUT VIETNAM

In the deep red soil surrounding

Wahiawā, Kunia, Poamoho

and Kūkaniloko, the birthing heiau,

teenagers do summer field labor.

We learned the disciplines of planting,

trimming (“cutting slip”),

weeding (“hoe hana”),

harvesting (“make quota”),

and of relaxation, posture, breath:

bend, pick a pine, repeat.

Behind, conveyor belt boom

that reaches over endless

rows of pine.

First a push, then a pull, then

the splattering of a rotten pine,

infested with black pineapple bugs,

across Mikey’s chest and face.

In a rage, he grabs more overripe pines

and begins throwing them at everyone.

One hits Ignacio, the tractor driver.

Tolentino, the luna, stands behind the tractor.

Then Funai leaps over a row of pine

and pushes Mikey hard onto the red dirt road.

Funai clenches his fists,

moves them in slow rotation,

and locks his arms in place,

one fist pointed to the ground,

halfway to where Mikey stands,

the other fist near his waist.

We had seen the movies

and knew how lethal fists could be.

Silence, brief stillness.

Tolentino forces a loud, long laugh.

And the whole gang lines back up behind the boom.

After that day, we didn’t see Mikey or Funai again.

Someone said the bosses made Funai a luna,

that Mikey worked night shift,

that they both got drafted and sent to Vietnam.

Summer, 1967

FROGSPAWN

Naval recruit training, San Diego, 1967.

Old Frog as young drill instructor,

known then as Froggy, having no visible neck.

Entire company inside concrete bunker.

Lesson: surviving fire at sea.

Froggy steps outside and shuts the metal door.

Fire! Fire! I remember the door.

Cover mouth with shirt.

Eyes useless, shut. Black, black.

Door, others already there.

Hot. Hot. Then suddenly opens.

We swim into the cold, fresh air.

Froggy yells, fall in, fall in.

We march toward nearby beach,

across rocks and sand.

Sound of waves approaching.

Carefully polished boots fill with

sand, cold water.

Waves now pushing us over.

Taking off boots.

Trying to stay afloat.

Now thrashing,

trying to swim,

to breathe, to breathe.

Jim Kraus lives in Honolulu. His poetry has appeared in Hawai’i Review, Kinalamten Gi Pasifiku Anthology (Guam), Poetry Hawai’i, Bamboo Ridge, Kentucky Poetry Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, San Marcos Review, Cape Rock Poetry Review, Neologism, Voices de la Luna, Another Voice and elsewhere. He earned a PhD in American Studies with specialization in environmental poetry from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. Currently, he is Professor of English at Chaminade University, where he teaches creative writing, environmental literature and surf studies. He also edits Chaminade Literary Review. He enjoys swimming, surfing, visiting art galleries and museums, and reading contemporary poetry.

Imaikalani Kalahele

Brandy Nālani McDougall

MEMORY

The kūpuna are all around us now,

caressing the grasses, the leaves

on each branch—they wonʻt let go,

just yet. Their dance makes the wind

brush the clouds across the sky—

strokes of an orangish hue

reflected in the gold of your eyes.

It is summer, a quiet breath

before the rain, and I am reminded

of how often they would say

the rain belonged to Wākea

as he reached for Papa through

the waves of air and miles of night.

But that was in the time before words—

the land, only a recent memory to the sky.

WATER REMEMBERS

Waikīkī was once a fertile marshland

ahupuaʻa, mountain water gushing

from the valleys of Makiki, Mānoa,

Pālolo, Waiʻalae, and Wailupe

to meet ocean water. Seeing such

wealth, Kānaka planted hundreds

of fields of kalo, ʻuala, ʻulu in the uka,

built fishponds in the muliwai.

Waikīkī fed Oʻahu people for generations

so easily that its ocean raised surfers,

hailed the highest of aliʻi to its shores.

Waikīkī is now a miasma of concrete

and asphalt, its waters drained

into a canal dividing tourist from resident.

The mountain’s springs and waterfalls,

trickle where they are allowed to flow,

and left stagnant elsewhere, pullulate

with staphylococcus. In the uplands,

the fields and have long been dismantled,

their rock terraces and heiau looted

to build the walls of multi-million dollar

houses with panoramic Diamond Head

and/or ocean views. Closer to the ocean,

hotels fester like pustules, the sand

stolen from other ʻāina to manufacture

the beaches, seawalls maintained

to keep the sand in, so suntan-oiled

tourists can laze on what never was,

what never should have been. No one

is fed plants and fish from this ʻāina now—

its land value has grown so that nothing

but money can be grown—its waters unpotable, polluted.

Each year as heavy rainfalls flood the valleys,

spill over gulches, slide the foundations

of overpriced houses, invade sewage pipes

and send brown water runoff to the ocean,

the king tides roll in, higher in its warming,

lingering longer and breaking through

sandbags and barricades, eroding the resorts.

This is not the end of civilization, but

a return to one. Only the water insisting

on what it should always have, spreading

its liniment over infected wounds. Only

the water rising above us, reteaching us

wealth and remembering its name.

Brandy Nālani McDougall is the author of a poetry collection, The Salt-Wind, Ka Makani Paʻakai, the co-founder of Ala Press. Her book Finding Meaning: Kaona and Contemporary Hawaiian Literature, is the first extensive study of contemporary Hawaiian literature. She is an Associate Professor of American Studies (specializing in Indigenous studies) at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Imaikalani Kalahele

CONTACT ZONE

Contact

That’s when two stuff

Touch, yeah?

Just like when the tides come in

And touch the shores

Bringing what it will.

Fish from the deep

Limu from the shores

‘Opihi from the rocks

Coconuts on the drift

Logs from the continent

People from around the world

Plastics and ‘opala of all sorts.

The shore has no choice

It has to accept

Whatever the tides bring.

Here we are

In this swirling muliwai

Of ideas and mana’o

Philosophies and spiritualities.

Like the tides

Ebbing and flowing

The shore has no choice.

But we do!

Imaikalani Kalahele is a Kanaka Maoli (native Hawaiian) poet, artist, and musician, whose poetry and art has appeared in literary & art magazines and in anthologies. He has read his written works at many literary readings, and his artwork has been exhibited widely in Hawai’i, and has also been exhibited nationally and internationally. He is the author of Kalahele, a book of poetry, and is the driving force behind the classic innovative War End Peace, an improvisational rendering of his experimental music-poetry, which can be viewed on YouTube via Mokaki.

Haunani-Kay Trask

A GIFT

together, cleansing each

other, tongue to eye

bruised blue souls

we learn the ache

in the knowing of it.

how the lash

curves inward

flesh to spirit

how violence seeks love

violating life

how rage at the world

burns through to the bone

brother, sweet brother

spirit wants peace:

our great slow ocean

tangles of cloud

the long calm

of late noon light

and this bud, this pua

this handful of sea

meditate on these.

WAI’ALE’ALE

who will rejoice in the rain

with me, softly piercing rain

wreathed in mist

and lehua from

the billowing upland?

My beloved companion of the purest water

wai aniani

caught in the bosom of the taro

wai ‘apo

who will rejoice at the breast

of the rain, o softness of my heart

cling to the slippery leaf

of the wai a kea?

Haunani-Kay Trask (October 3, 1949 – July 3, 2021) was a Native Hawaiian activist, educator, author, and poet. She served as one of the leaders of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and was professor emeritus at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. She was a founder of the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and served as its director for almost ten years. Trask published two books of poetry, Light in the Crevice Never Seen and Night Is a Sharkskin Drum. Her poetry was published widely in literary publications and anthologies.

Mahealani Wendt

CALVARY AT ‘ANAEHO’OMALU

In a hotel lobby

Near ‘Anaeho’omalu Bay

A resort manager’s grand idea

Of Christmas in Hawai’i –

A two story Norfolk

Festooned with implements

Of Hawaiian dance:

Feather gourds, ‘uli’uli,

Gaily colored and fastened

With braided hau;

Double gourds, ipu heke,

Suspended by intricate netting;

Split bamboo, pu’ili,

Backdrop of kapa –

All gifts from an

Ancient intelligence,

The whole show

Razzle dazzle electric,

Undulating, haole hula,

In soft offshore breezes.

I stand at Christ’s tree

And from another temple

Illuminated by oils of kukui hele po

And the moon goddess Hina,

An intoxication of holy communion:

From a stranger’s silver chalice pours

The dark blood of ancestors.

Pulsating

Blood and sinew

Sensate with the drumming of pahu,

Clash of ka la’au,

Rattle of kupe’e,

Rapping of ipu heke;

Voices rise out of shadows

And intone an ancient cadence.

E Laka e (Oh Laka

Pupu weuweu Oh wild wood bouquet

E Lake e Oh Laka

‘Ano’ai aloha e Greetings and salutations

‘Ano’ai aloha e Greetings and salutations

‘Ano’ai aloha e Greetings and salutations)

In a hotel lobby

‘Anaeho’omalu spinning,

I feel tethered and hammered through,

Wild among dark branches

Snared by voices on angry winds.

LILI’U

We are singing a requiem for our mother,

Our voices a shroud across this land

Wrenched we were, from Kamaka’eha’s soft bosom,

Wretched, our grief inconsolable

We are feeble scratchings against cold granite vaults,

Grasping, tremulous as moondark trees,

Our fire-spirits burned black as cinders –

Our mouths filled with ash.

Our mother’s spirit was incandescent colour, Green

Ocean of emerald stars, mosses, living grass:

Know you our sweet-voiced mother?

Know you her children’s sorrow?

Cloudless azure, blue-veined petal:

Her blood was a firebrand night,

Her bones iridescent light;

She sang the sunlit bird.

Fire-spirits burned black as cinders,

Mouths filled with ash,

We search the empty garden, Uluhaimalama,

Papery flowers on melancholy earth. Now

Our song is for our mother,

Our nation,

Our rebirth.

Mahealani Wendt is a Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) poet, writer and community activist residing in Hawai’i, on the island of Maui. In 1993 she was the recipient of the Eliot Cades literary award for an emerging writer, and is the author of the poetry collection Uluhaimalama and other publications. She recently retired as the executive director of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, a public-interest law firm specializing in Kanaka Maoli rights. She has worked for Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation since 1978. Her poetry has been published widely in literary magazines and anthologies.

Craig Santos Perez

ECL (English as a Colonial Language, an abecedarian)

American authorities

banned

Chamoru language to manifest

destiny :

English enforced at the empire’s

frontier of “freedom.”

Guåhan means “we

have,” but what is home-

island if silenced by the violent

jingoism of an unjust

klepto-settler state––if

language is stolen from our living

mouths &

nouns reduced to nothing––if

oceanic throats &

pasifika palates pacified––

quiet like i halom tano’

ravaged by brown tree

snakes swallowing i

totot, sihek, åga…

until ancestral

vowels & consonants, once avian

wild, now

xtirpated––

yielding to the colonial

zoo of endangered tongues.

The Pacific Written Tradition

I read aloud from my new book

to an English class at one of Guam’s

public high schools. Afterwards, I

notice a student crying. “What’s wrong?”

I ask. She says, “I’ve never seen our culture

in a book before. I just thought we weren’t

worthy of literature.” How many young

islanders have dived into the depths

of a book, only to find bleached coral

and emptiness? We were taught

that missionaries were the first readers

in the Pacific because they could decipher

the strange signs of the Bible. We were taught

that missionaries were the first authors

in the Pacific because they possessed

the authority of written words. Today,

studies show that islander students

read and write below grade level.

“It’s natural,” experts claim. “Your ancestors

were an illiterate, oral people.” Do not

believe their claims. Our ancestors deciphered

signs in nature, interpreted star formations

and sun positions, cloud and wind patterns,

wave currents and ocean efflorescence.

That’s why master navigator Papa Mau

once said: “if you can read the ocean

you will never be lost.” Now let me tell you

about Pacific written traditions, how our ancestors

tattooed their skin with scripts of intricately

inked genealogy; how they carved epics

into hard wood with a sharpened point,

their hands, and the pressure and responsibility

of memory; and how they stenciled

petroglyphic lyrics on cave walls with clay,

fire, and smoke. So the next time someone

tells you our people were illiterate, teach them

about our visual literacies, our skill to read

the intertextual sacredness

of all things. And always remember:

if we can write the ocean, we will never be silenced.

Craig Santos Perez is a Chamoru from Guahan (Guam). He is the author of six books of poetry and the co-editor of six anthologies. He is a professor in the English department at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

John Costello

Tony Quagliano

THE TEETH OF THE MASK.

When I talked with Jack Lahui on his way back

to Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea

from his third world or eighth world

literary invitation to poetry in Iowa

his first visit to America

he told me most everything was strange

he asked me at the Pali lookout here

on Oahu

“how many different

kinds of cars does America have?”

and why on stage in Iowa

a famous American poet

wears primitive masks?

I stood there in the Pali wind

American, and local guide

despairing of cross-cultural understanding—

I had just recently learned

that I was a haole

and I didn’t know how many kinds of cars

or about the poet in the mask

or why these were Jack’s questions

or what my answers could have meant—

we drove on over to Kailua

in my 1965 six cylinder

light blue four door

Dodge Dart sedan

Tony Quagliano (1941-2007) was an experimental poet and editor. His work was innovative in pushing the boundaries of poetry in general with his experimental approaches to form and language. As a poet, essayist, literary critic, jazz writer, and editor, he was widely published. Quagliano was a professor of American Studies at Japan American Institute for Management Science at the University of Hawai’i.

John Costello (1950-2015) was born in New York and studied at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. He moved to the North Shore of the island of O’ahu in Hawai’i in the early 70s, and opened Ka’ala Art Gallery in the North Shore town of Hale’iwa in 1980. Costello painted extensively in the years he worked and lived in Hale’iwa. During this time he also travelled to the South Pacific and exhibited his art in Aotearoa, Tahiti, and on the island of Raratonga. In the late 1990s Costello relocated to the neighbor island of Maui, and lived in Hana and Kipahulu until his passing. Costello also created works as a wood carver, and he enjoyed playing music on a small lap held harp.

Shinichi Takahashi

H. Doug Matsuoka

AND FINALLY—PARADISE

an excerpt

It could have been his absent-minded grasp that let the test tube slip from his hand onto the scuffed mahogany planking of the floor. Small fragments of glass crackled under his boots as he walked toward the eastern end of the lab to open a window. He wanted to let some air in and get a look at the surrounding fields of marijuana that had finally become familiar to him.

As a test, before opening the window, he closed his eyes and tried to visualize the scene that he hoped would confront him. The ridges of the Koolau mountain range, the valley, the fields on the slope, and to his extreme right, in the distance, the Pacific Ocean. He filled in his mental outline with color. The glossy green of the plants, brown almost black dirt between the rows, the severe violet of the Hawaiian sky and Hawaiian ocean (both fringed with white), and the piercing brightness of the unseen sun.

For the past twelve years he had given painstaking attention to the surrounding scenery. He observed and memorized the contour of the slope, every little tooth in the ridge, every modulation of color, every crooked line of shadow until the image embedded itself ineradicably in his memory creating a mental holograph of geography that he could exist in with a limited yet definite certainty.

He opened his eyes—it was all there. A wave of relief broke over him and he took a deep breath.

“Nick? . . . Dr. Nicholson?’ A voice calling him from the doorway of the lab. “Dr. Nicholson. It’s me, Nelson. Nelson Yamamoto. Remember me? Listen, can I talk with you for a second?”

What choice was there? But he said nothing. He kept looking out the window, peering toward the ocean. It was inevitable that his next station would be on the ocean. The agricultural project was over and they needed competent mentalities working the whale pens.

He commanded himself not to think about it. He looked up: the stars would be out tonight.

From Dr. Yamamoto’s Report—7 December XXXVII:

The Hawaii Agricultural Association’s Special Botanical Project, under the direction of Dr. Francis “Nick” Nicholson, has been a complete success. However, our data shows that Nicholson has not responded in a manner consistent with the predicted forecast (analog one one zero seven group Alpha). What is especially disturbing is the marked and continuous rate of down trending evident in the charts accompanying this report. The following transcription of the recorded conversation I had with him earlier today is illuminating in that it helps to show the basic manifestations of his problem.

Y. Nick, I know there’s a problem. A blind man could see it with a cane. The thing is, Nick, we don’t know just what it is. Look we’re friends aren’t we. What’s going on?

N: (Pause) We were friends. Once. Before they changed it.

Y: (He is referring to the period previous to March XXXV when I was a co-worker on the project)— The project, your project, was a success. You did it. There’s always more work to be done. Especially by a man of your caliber.

N: (No response)

Y: Governor Loo even sent you a public letter of praise. Doesn’t that mean anything to you? Listen. I’ve heard that the whale project needs a coordinator. You could take it if you wanted it. It would help make Hawaii independent of outside sources as far as food is concerned.

N: Yeah. Too bad about Fong and all.

Y: Fong was asking for it. He was a fool, an incompetent. One of the cortical implants was adjusted wrong and he failed to check, failed to follow procedure, failed to follow routine. The psyche fields had no effect whatsoever on that whale.

N: Hell of a way to go. Crushed and dismembered by a berserk whale. Whatever happened to the whale anyway? Did they catch him?

Y: They caught him alright. He’s probably on the market by now.

N: Eight seventy-five a pound at Star Supermarket.

Y: It’s around nine twenty now. Demand went up a click after the incident.

N: Whales used to be strong and graceful animals. The sleekest, most beautiful goddamned things in the ocean. Now they’re so fat and bloated they drown when the sea gets a little rough. Kept in invisible pens by little implants in their brains and transmitters in the water . . .

Y: Look Nick. There are still a lot of whales in the wild. We just breed a few so we can survive, so that they can survive too. We use every bit. Every organ, every square inch of skin, every fiber of gristle and cartilage, every ounce of flesh. We don’t waste anything. It’s not wanton slaughter. And I’ve noticed that you’re no vegetarian. I never seen you turn down a good steak.

N: The Hawaiians had a whale god. Did you know that?

Y: I wouldn’t doubt it.

N: Whatever happened to the Hawaiians? That’s a question, Doc. Whatever happened to them?

Y: What do you mean? They’re still around. Thompson, your senior assistant, he’s part-Hawaiian— You know that. Hawaiians and part-Hawaiians comprise a full five percent of our population. You must know- –

N: – -I mean, what happened to the old time Hawaiians? Their language and chants, their ways, orientations . . . their history. Their gods.

Y: Old time Hawaiians adapted to the modern world. Ancient Hawaiians can only exist in the ancient world. And I don’t think your problem has anything to do with Hawaiians at all. Maybe you feel guilty about being white. Or you’re just trying to throw me off. Right?

N: (No response)

Y: Nick. Take a break. Celebrate. Go out and have a good time. Just for one night. And then, tomorrow, you can come back and worry about whatever you want to worry about, think about whatever you want to think about. You can come back and think about God for the rest of your life if you want. Our Lady of Peace needs a new Monsignor. Nichiren needs a priest. You’re a big man now. You can have any post you want. But tonight, go to Waikiki and have some fun.

I’m not supposed to say anything, I’m not supposed to tell anyone about it, it’s classified, but I’ll tell you anyway. There’s a Holiday scheduled for tonight. And a big one too, for what I can tell. I’d go down there myself if I could get away from the monitors. Go down to Waikiki tonight Nick.

N: (Pause) No, I don’t think so, Doc.

Y: Yes, I think so, Nick.

N: That’s the prescription then?

Y: Yes, that’s the prescription.

N: I figured I was a candidate for restructuring.

Y: I don’t think you need anything that radical. I honestly don’t. A night in town, away from this broken down agricultural research facility or whatever the official name is, will do the trick, I think. The excitement of the holiday will do it.

N: What kind of Holiday?

Y: That part must remain a secret or it’s no fun.

N: Makahiki?

Y: What?

N: Nothing, nothing. I’ll go.

Y: Good. And Nick, come see me in the morning, okay?

N: Sure Doc. Anything you say.

Dr. Yamamoto in summary regarding Report—7 December XXXVII:

Y: I think that there is a chance that the holiday will do him good. It is my hope that the excitement will spark a kind of third level catharsis that will result in the realignment of the affected components in a spontaneous restructuring of the total psychic spectrum. I want to give that a chance before recommending a passive restructuring, which would be very risky in Nicholson’s case.

Just the same, I think that the chance of him spontaneously restructuring is very small, and I have already reserved time/space at the State Hospital at Kaneohe for him starting the day after tomorrow, 9 December XXXVII

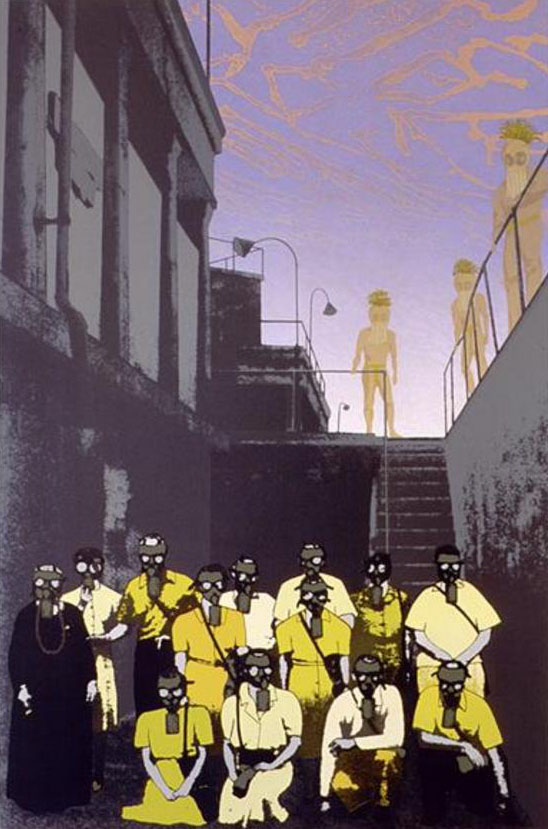

Shinichi Ola Takahashi is from the Miyagi prefecture of Japan. He studied at Aoyama Art School and the Kuwazawa Design School in Tokyo. In 1971 he had a one-man show at the Ginza. During this period he became captivated by “Nihon-ga” (Japanese-style paintings) and soon fell into a period of creating religious paintings, particularly focused on “Jigoku-e” (hell scenes). Takahashi immigrated to Hawai’i in 1974 to become a pupil of Jean Charlot (1898-1979), a well-known Hawai’i mural artist. His view of art vastly developed in Hawai’i as he became engrossed in Western art movements like Cubism, Surrealism and DADAism. More on Takahashi’s work can be found at shintakahashi.com

H. Doug Matsuoka was born in Hilo, Hawai’i, and graduated from Kalani High School in 1970. Matsuoka is a writer and musician, among many other creative impressions. His serious interest in music came late—in his mid/late teens but he did initially study music theory and composition at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, before dropping out thinking he was smarter and more talented than he really was. Over the years he has been a musician in bands, notably The Hawai’i Amplified Poetry Ensemble, a writer, a gas station pump jockey, a computer guy, a basket case…all sorts of things which is what happens if you live a long time. This early version of “And Finally—Paradise,” was written in the late 1970s, and comes from some earlier acid trips through Waikiki, where Matsuoka tried escaping UFOs that were pursuing him by diving under parked cars.

Wayne Westlake

Wayne Kaumualii Westlake (1947-1984), is an internationally published Native Hawaiian poet whose work continues to be exhibited and published worldwide.

Westlake, Poems by Wayne Kaumualii Westlake, co-edited by Mei-Li Siy and Richard Hamasaki, was published by the University of Hawai’i Press. Westlake was an avid supporter of Native Hawaiian causes and issues, and his creative energy on such matters, was often channeled into his poetry, concrete poetry, essays, research,

and editing.

Richard Hamasaki

ARTIFICIAL CURIOSITIES

Low grumble of earth

trembling mountains

and everything quakes

a prolonged shiver that rattles the world

From below the foundations

of a plantation-style cottage, there is a low humming sound

that won’t disappear, a murmuring almost imperceptible

then the shaking subsides but does not stop

At this moment, there are no

trans-Pacific flights

off Diamond Head

approaching the reef runway,

but I can hear my neighbor,

an elementary school principal,

shrieking

at his 8-year old son

From where does this low hum originate?

not from the steady stream of cars

cruising the streets

Museums displaying

fine specimens,

striking colors sealed in

controlled environments:

Reading

Artificial Curiosities

“An Exposition of Native Manufacturers

Collected on the Three Pacific Voyages

Of Captain James Cook, R.N.”

thumbing my way

toward a section called

“Owhyhee or the Sandwich Isles.

Living images,

housed in museums and collections

throughout the world

documented, catalogued

and “safe”

protected so long as they remain

“artifacts” which can maintain traceable, pedigreed ancestries:

Artificial Curiosities

Vienna: “Feathered temple”

Leningrad: “Makaloa mat”

Greenwich: “Hawaiian spear”

Anonymous Private Collection: “Bowl with human images”

Berlin: “Feathered image”

Cambridge: “Two bracelets of turtle shell, dog teeth and ivory”

London: “Gourd rattle”

Edinburgh: “Shark tooth implement”

Glasgow: “Drum”

Dublin: “Idol’s eyes”

John Hewett Collection: “Barkcloth piece from bound volume”

Cape Town: “Feathered Helmet”

Sydney: “Netting sample for feather cape”

Honolulu: “Dagger”

Artificial Curiosities

Plant-dyed kapa, scented with extracts of flowers,

fragrant woods or leaves from Laka’s vine;

Polished wood-smooth tools and sharks’ teeth;

musical instruments worn like personal adornments;

Weapons and apparel of power;

religion of gods and feather dwellings

“Artificial Curiosities”?

Low rumbling thunder, distant,

within the earth

Scraping of stone blade upon rock.

Incandescence of amber rape lights

Interior illumination, the red-eyed video camera

From beneath the decaying cities,

museum walls shatter,

splintering display cases,

hum of magic, words melting words, images

transfusing red mulberry dye,

disintegrating, transforming

Foundations crumble, brittle;

car-splitting thunder

Towering mountain faces,

a blackened night sky issuing flashes of light.

Tendons straining,

mother-of-pearl eyes and mouths agape,

jagged tongues of lightning,

and the “bowl with human images” appears

above the vast portals, twin tunnels, grey concrete vaults collapsing

beneath the white-toothed mouths, blood red and gaping.

Two valleys of concrete and steel collapse,

and rising from mountain peaks

mammoth sculptures;

emerging human images of rock, skin like dyed kapa, dark as earth,

crouching, luminescent eyes, wide, like pohaku kekea,

arms and feet rooted in stone and earth yet bursting upward

swallowing strips of towering highway,

like a ribbon of clouds above the valley floors

the crushing weight of countless waterfalls

roaring from multi-fingered fisted cliffs

Museum pieces

as tall as mountains

as alive as

hurricane wind

and endless downpour

of rain

Artificial Curiosities, indeed

…artificial curiosities…

Are you

an artificial curiosity?

Richard Hamasaki is the author of Spider Bone Diaries, Poems and Songs, which was published by the University of Hawai’i Press. His poem “Artificial Curiosities,” is a selection from that book. He co-founded ‘Elepaio Press with his brother Mark Hamasaki, a photographer, book designer and printer. The first publication that the then new press put out, was Seaweeds and Constructions (1976-1984), which was, and is, an art and literary magazine of Hawai’i. The creative idea and energy, of the Hamasaki brothers, joined with featured co-editors Paul L. Oliveira and Wayne Kaumualii Westlake, along with artists Shinichi Takahashi, Kimie Takahashi, and many other contributors, which included such creative writers as Joe Balaz and H. Doug Matsuoka, to establish the magazine as an innovative and groundbreaking artistic expression of its time.

Laura Ruby

Orchid Tierney

prayer | suit

In Carbon County, the petronauts caw

to clear trees for the PennEast pipeline,

they say they have concerns about

contaminated air and groundwater,

mud swamps and wild trout streams,

unspoiled brooks to dip their feet in,

they say they can safely transport gas,

as a mausoleum of faculty,

and bring 12,000 jobs to the county,

they say they will post no trespassing signs

and conduct town hall meetings, distribute angry flyers

build websites and call radio stations

to raise public awareness,

they say natural gas is green like clean coal

and their teams live there,

they say they are citizens too

like bald eagles and bobolinks, bobcats and harrier hawks,

herons and cormorants, whose wetlands and parks are now at risk,

they say they will seize private and preserved lands using eminent domain,

they say Molly Maguire will fill their chests with smoke and culm,

stir up wasp nests in hillocks of black snow, because

everybody’s goal is mine more coal,

they say this is proof of my words. That mark will never be wiped out

this is your hous, notice you have carried this

as far as you can by cheating from a stranger he knows you,

so they prayed: o dear lord, please help us stop the pipeline, amen,

“Say, now you’re cooking with gas”

Orchid Tierney is a poet and scholar from Aotearoa-New Zealand, now residing in Gambier, Ohio. Her chapbooks include Brachiation, The World in Small Parts, Gallipoli Diaries, and the full length sound translation of Margery Kemp, earsay. First collection, a year of misreading the wildcats, is out from The Operating System. She received an MCW from the University of Auckland, an MA from University of Otago, and a PhD in English from the University of Pennsylvania. She is Assistant Professor of English at Kenyon College in Ohio.

Laura Ruby is a Hawai’i Living Treasure Honoree and a recipient of the Hawai’i Individual Artist Fellowship Award, and has exhibited her work widely. Her prints and sculptures have been shown in national and international juried and invitational exhibitions. She recently was a professor in the Art History department at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where she taught art and honors in a long career that has spanned a little more than three decades.

Lee A. Tonouchi

SIGNIFICANT MOMENTS IN DA LIFE OF ORIENTAL FADDAH

AND SON: COLLEGE

Aftah I wen graduate high school

my Oriental Faddah

wanted me

for go

Harvard, Princeton, Stanford,

AND Yale.

He nevah know

wea any of those places wuz,

jus dat das wea I had fo’ go.

So I went

UC Irvine.

Das wea I wen discover

dat my Oriental Faddah

wuzn’t really

my Oriental Faddah.

He wuz my

“Asian American” Faddah.

Dey sed I can have one Oriental rug

or some Oriental furnitures,

but I cannot

CAN

NOT

have

one Oriental Faddah.

Oriental is one term you use

for da kine inanimate objecks.

Das wot dey toll me.

So, I toll ‘em

“Oh, my Oriental Faddah,

he hardly sez anyting.

Das kinda like being

one inanimate objeck, ah,

Wotchoo tink?”

Ho, when I sed dat

their faces wen jus

freeeeeze,

like dey couldn’t believe

I sed someting

as disrespeckful as dat.

Tsk, “Asian American” das why.

SIGNIFCANT MOMENTS IN DA LIFE OF ORIENTAL FADDAH

AND SON: MARRIAGE

I came back home

wit one girlfriend

fiancée actually

who wuz one katonk.

Only she nevah know she wuz

one katonk.

She probably mo’ used to

da term

banana.

Either way, my Oriental Faddah

wuz happy

katonk, banana,

TWINKIE,

so long as Oriental he sed.

“Asian American,” she correck-ed.

Jus for fun

I took her to one

Frank Delima show

at da Polynesian Palace.

But she nevah laugh,

not even one chuckle

for wot she called

“the blatant

stereotyping and racist

ethnic portrayals.”

So I started playing around, brah.

Aftah da show,

I started telling all my friends

“Eh, wassup Oriental!”

“Ooo, you friggin’ Oriental!”

“Brah, yo’ Mama, she so Oriental

I bet she cannot see her chopsticks

unless she turn ‘em sideways!”

I figgah I would take back

da term!

If Popolo people can

use da “N” word, den hakum

I cannot use da one

dat starts wit “O?”

ENPOWERING li’dat.

She tot I wuz nuts.

Out of my freakin’ mind!

So she got back on her plane

and left.

Looking in da air

all I could tink wuz

Wot Lucille,

You going leave me now?!

Even though Lucille

wuzn’t even

her name.

Lee A. Tonouchi stay one Okinawan yonsei from Hawai’i known for writing in

Hawai’i Creole English. His poetry collection Significant Moments in da Life of Oriental Faddah and Son: One Hawai’i Okinawan Journal won da 2013 Association For Asian American Studies Book Award. Most recently he stay da recipient of da 2021-2022 Tony Quagliano Poetry Award and da 2023 American Association for Applied Linguistics Distinguished Public Service Award for his work in raising public awareness of important language-related issues and promoting linguistic social justice.

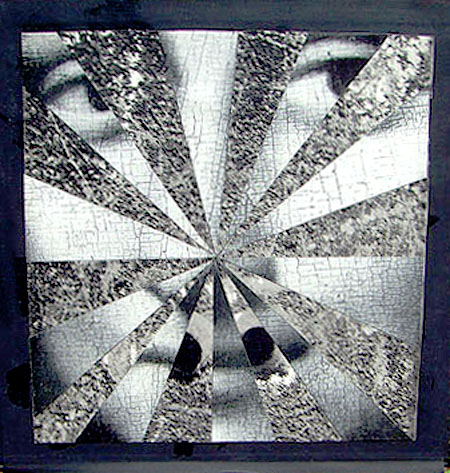

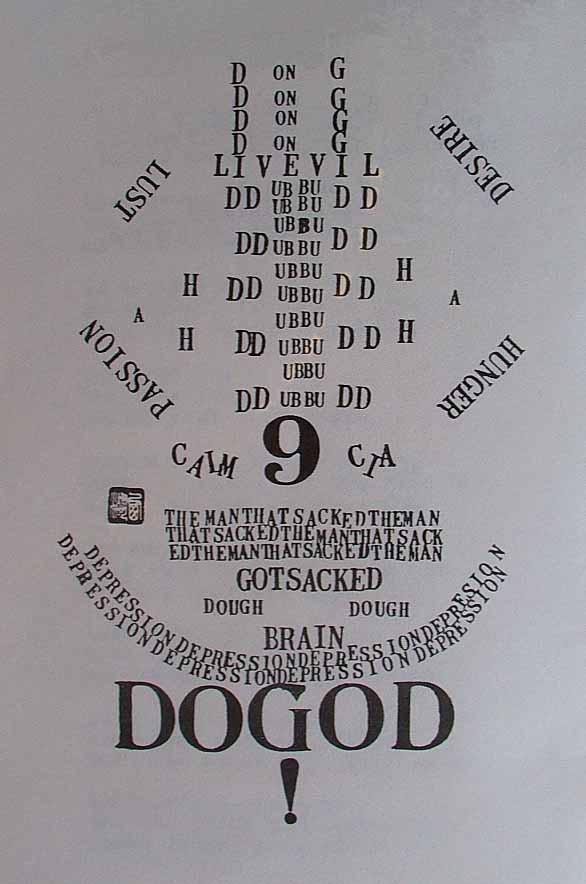

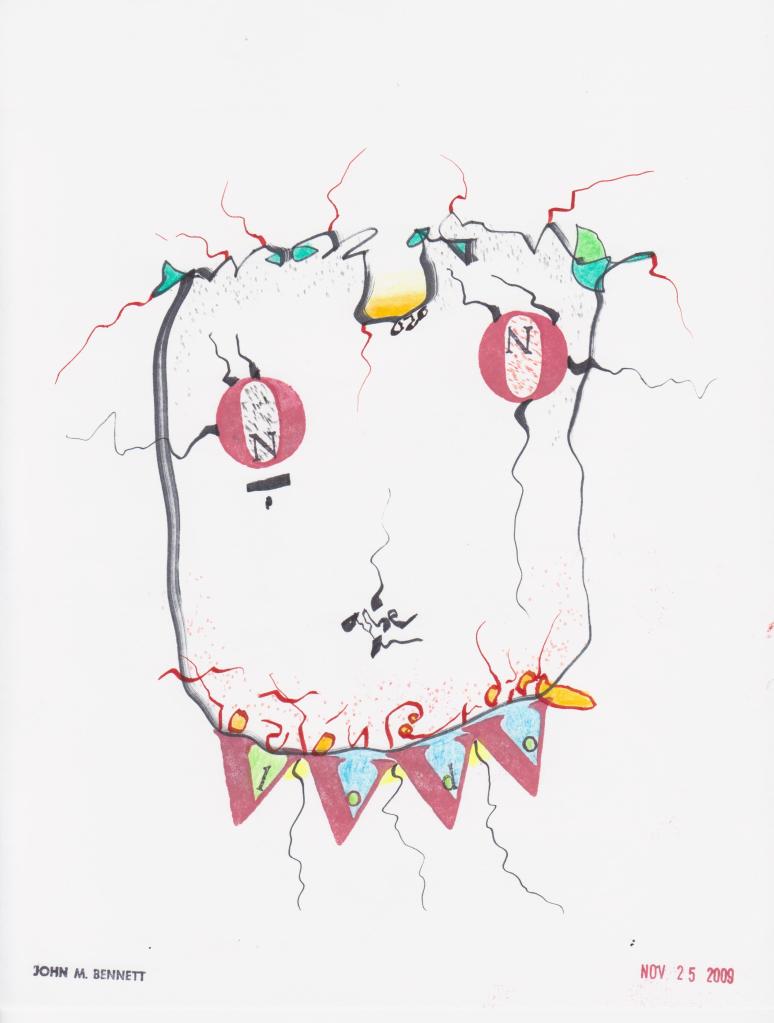

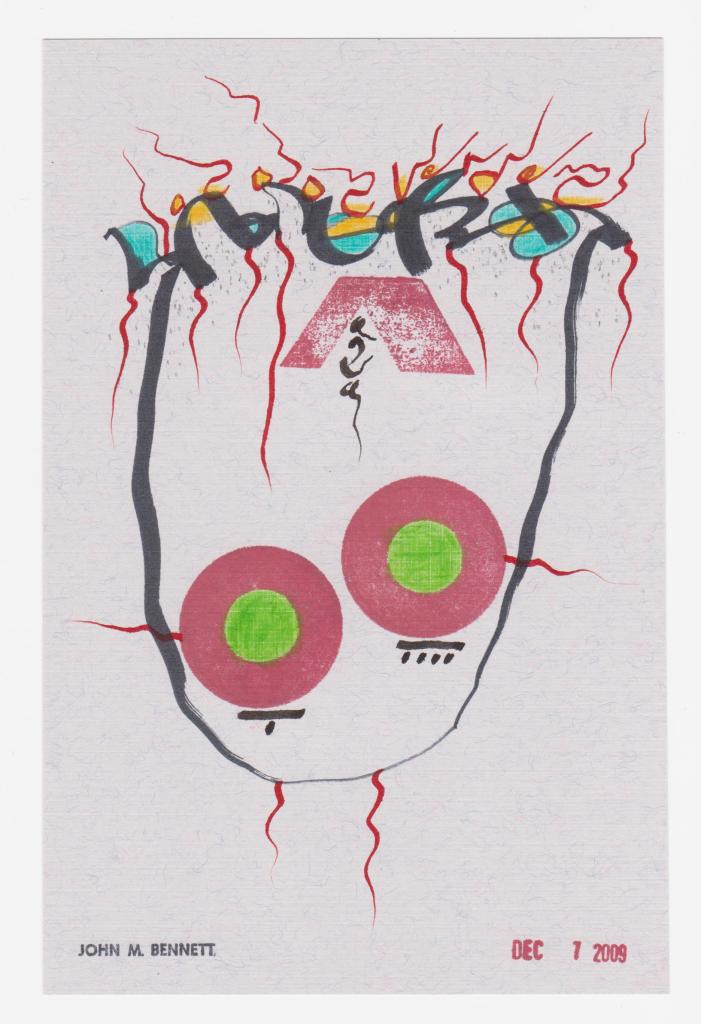

John M. Bennett

Maya Heads

John M. Bennett has been widely published, and has exhibited and performed his word art worldwide in numerous publications and venues. He was the editor and publisher of Lost and Found Times, from the middle 1970s to the early 2000s, and he is the Curator of the Avant Writing Collection at The Ohio State University Libraries. He has a PhD in Latin American Literature and lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Jason Floyd Williams

last stop.

We’re three months early for the Last Stop Willoughby Festival,

so we wait at a local diner.

Barry is two stools away from us.

He introduces himself.

He’s a restaurant regular.

A neighborhood fixture.

You can tell.

Third sentence into his biography is he’s dying.

Bone cancer.

Three years to live.

Age 60.

Barry incubated with fluorescent lights.

Barry raised with ink toners & filing cabinets.

Barry with his translucent thin skin throbbing

to “I think we’re alone now” on the jukebox.

Barry whose Sears Roebuck dress shirt, & matching pants,

reveals a life in accounting; a life indoors; always indoors.

A plastic houseplant.

Barry combs back his receding shrubbery hair & leans in closer,

Covid-catching-closer, and says he’s afraid to die alone.

That’s why he’s pursuing younger women, 20-30 yrs old.

Like that cute blond over there, he points curled finger.

She’s with a Beefcake boyfriend.

They glance over our way.

I tell the waitress to make our food to go.

Mary Ellen Derwis

unseen luggage.

Shane was waiting outside my shop, 15 minutes before we opened.

It was 35 degrees out.

He’s wearing a dark, sleeveless flannel,

gray scarf around neck, & his bare arms are littered with Egon Schiele-jigsaw-tattoos-designed-70s-

rock-album-covers.

We’re both wearing our cheap blue disposable masks

cause it’s the days of Covid.

I invite him into the shop.

I ask him how things are with his back.

He was getting nerve block & maybe some vertebrae fused last time we talked.

He’s doing more regular shots nowadays, no surgery scheduled. Too tricky.

What messed up your back? I ask.

Work, genetics?

This was a Kerouac cosplayer valve release of an almost hypnotic regression:

“It may have been when my mother, an awful woman, threw me through a glass table.

I was four years old.

Or when she kicked me down the stairs.

I was a little older.

I remember that one vividly.

My mother & step-dad were terrible.

My step-dad tortured & killed my younger brother, Jack.

Chained Jack to the gas radiator; burned his skin.

Eventually the ol man choked poor Jack out.

Or, there was the time I flipped an18-Wheeler in Pittsburgh.

Took the exit too hard; spilled oil-contaminated soil all over the freeway.

Or, that time, a few years back, when that woman–texting–hit me

straight going 45mph…”

“Waitaminnut,” I interrupt.

“Your step-dad killed your brother?

I hope he went to jail.”

“Yeh,” Shane continued. “He did.

And the other prisoners didn’t like child killers.

They learned my step-dad had a metal plate in his head,

from a construction injury.

They waited for him in a jail corridor.

They waited for the guards’ shift change.

They waited for him to be alone.

They attacked him.

Kicked in his metal plate & killed him quickly.

I wasn’t upset when I heard that.

He was a terrible man.”

Jason Floyd Williams, like Bill Bixby from The Incredible Hulk TV series, often finds himself followed by sad piano music & hitchhiking, usually in the rain, from one Ohio town to the next. If you see him at a small town diner or bar, call the local sheriff. Some of his warrants may be attached to rewards.

Mary Ellen Derwis is a painter and photo artist, and her work has appeared in various publications online and in print. She was born and raised in Cleveland, and later lived in San Francisco, California, and in Hawai’i. She returned to live in Northeast Ohio for a little more than a decade, before recently moving to live in Virginia.

Luigi C. Russo

I KNEW IT

Once I kissed her pink lips

and touched her dark skin

I knew there would be trouble for me

I knew the green would turn brown on the trees

I knew it all along

I knew it all along

Just to walk with her, holding hands

would cause a stir among the lands

I knew there would be some strangeness for us

I knew the yellow paint could chip off the school bus

I knew it all along

I knew it all along

Since we been together everyday

nothing to separate us, nothing to betray

I knew there would be fires from those I know

I knew the sun would refuse to show

I knew it all along

I knew it all along.

Now the dark woman is a distance to travel

and my heart is hers, is hers, all

I knew there would be a troubled paradise

I knew thirteen would roll from the dice

I knew it all along

I knew it all along

Luigi C. Russo is a family man and library worker. He is the author

of several books of poetry. The poem “I Knew It” is from

Chorus Chorus Come To Me, one of his books of poetry. He lives

in Portage County, Ohio.

Peter Chamberlain

The Pictorial History of the Evolution of the Jazz Clarinet

as ReWritten by Mint Romkey

(A Tribute to Mezz Mezzrow)

Peter Chamberlain is an artist, musician, and educator. Throughout four decades of teaching and working in the areas of expanded arts and intermedia he has emphasized systemic structure: the structure of process, of production, of value systems, of composition, of the art world, etc. Content has mostly addressed unlikely juxtapositions between nature, culture, and technology. He has taught Expanded and Electronic Arts at the University of Hawai’i since 1991, and prior to that taught Sculpture and Video at Elmira College in New York State since 1976. He retired in August of 2022, and presently lives in Palolo, Hawai’i.

Chamberlain has widely exhibited and performed his work in Hawai’i, throughout the US, and internationally. A large extent of his expansive work can be found at:

peter-chamberlaingph8.squarespace.com

13 MILES FROM CLEVELAND

Edited by Joe Balaz

Joe Balaz lives in Northeast Ohio in the city of Cleveland. He edited Ramrod–A Literary and Art Journal of Hawai’i, and was also the editor of Ho’omanoa: An Anthology of Contemporary Hawaiian Literature.

All works appearing in 13 Miles from Cleveland are the sole property of their respective authors and artists and may not be reproduced in any way or form without their permission. © 2022.