Volume 5, Number 1 2023

PACIFIC ISLANDERS EDITION

John Dominis Holt

MANA

Not one voice

but many—

One voice is easily lost

in the electronic din of the air waves.

Not one arm

but many–

One arm alone

cannot awake the earth to green

in the torrid wastes of dusty drouth.

Not one dream for one alone

but many—

The dream of many moves

from troubled sleep to waking songs.

Not one song

for it is not enough

to cure these curious ills,

these torments of mind and body

which blight the earth.

Connections

cannot connect

disparate ends.

A steady throb

links ant to anthropoid,

and thin blades of grass

to towering koa trees

in their dampened paradise.

May the stars give us

the understanding of unison,

in which we all share mana

to endure the coming onslaughts.

Tamara Wong-Morrison

STRANGE SCENT

Hear the beating of the pahu

distant and warning.

Beware—a strange wave has washed upon the rocks

even the crabs run from their homes.

In the night it passed over shining black water, gliding—not

knowing where it came from

or where it’s going

An omnipresence—there.

Me, I tried to sleep under starless sky

but too dark

too strange

too still.

I feel I will never be the same again.

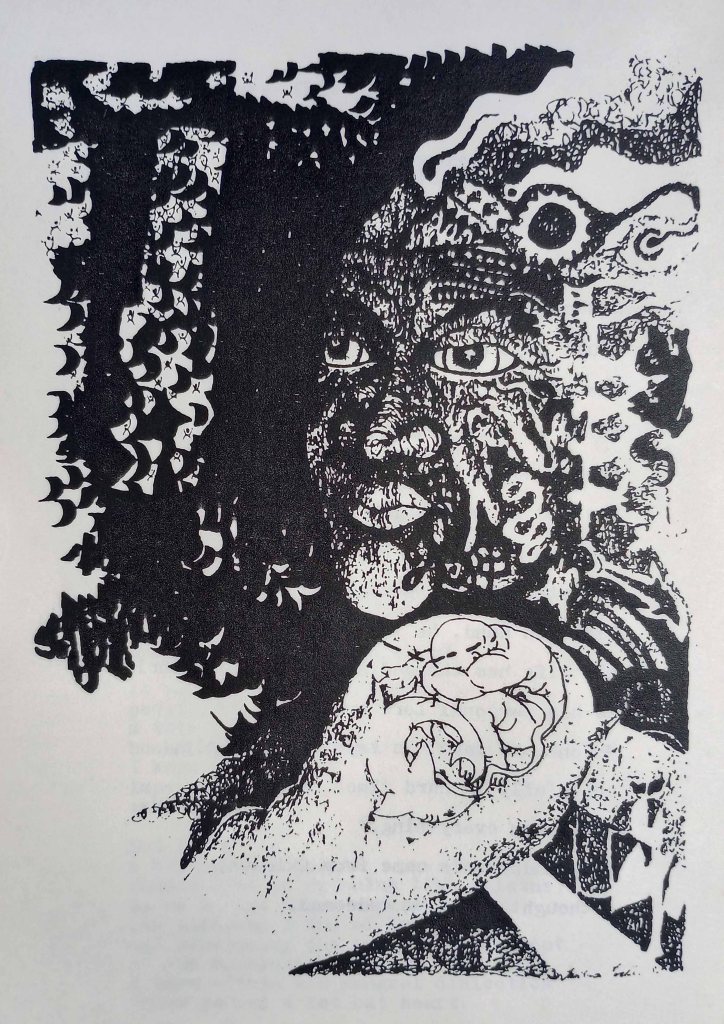

Imaikalani Kalahele

Chuck Souza

LAVA IN THEIR SOUL

Chuck Souza – guitar, vocals / Sam Henderson – guitar / Beau Leonidus – bass guitar Greg Kekipi -‘ukulele / Kevin Daley – drums / Creed Fernandez – congas, percussion Kurt Thompson – keyboards

Imaikalani Kalahele

John Dominis Holt

AUNTY’S ROCKS

I wondered Aunty

why you kept those rocks on the shelves

covered by a curtain?

Why you fed them brandy?

And why in the night

you cried out to the classical gods,

chanting in quiet tones

because of the nearness of neighbors?

I was frightened

awakening in the dark

to these incantations.

Where are the gods of old?

Why do you seek them?

Why not the Lord Jesus,

the Son of God,

who died for us

on that hill long ago?

Aunty

why do you wail

and form the weird tones

out of words so foreign

and unfriendly to a modern ear?

Why do you supplicate? Implore?!

Is it your jealousy of Kiliwehi,

whose beautiful voice

rises to the skies above the banyan

and the palm where you linger?

Kiliwehi,

Songbird of Hawai’i

she was called.

I once peeked

and saw three pōhaku on your shelves

with jiggers of Metaxis brandy

poured full in front of them.

Radioactivity made by your prayers

filled these rocks with evil powers:

a strange radiation of sorts

fissionable and lethal.

‘Unihipili was captured

and held in the mana of your invocations,

to be transformed into akua lele

awaiting their killing flights.

But Aunty

I also remember the time

in your living room

when you sat before a large calabash.

At the bottom

bits and pieces of Kiliwhehi’s possessions

lay quiet and compliant.

And though you would soon die

from the powerful rush

of carcinogenic unleashings in your liver,

you prayed continuously over that calabash

for the destruction of Kiliwehi.

Alas!

The ‘unihipili powers flew out

and chose you as their beloved victim.

All of us

were saddened by your death

as the whole town mourned—

And Kiliwehi

at your burial service

sang with such brilliance

and aching poignance,

before the heavy rains

fell in your honor

out of the sky.

Leialoha Apo Perkins

PLANTATION NON-SONG

Those years of lung-filling dust in Lahaina

of heat and humidity that induced

men and animals to lie down mid-afternoons

and sleep—between the mill’s lunch shift whistles—

were not great, but mediocre for most things

and superlative for doing or not doing anything

useful, ugly, or good. Just for staying out of trouble.

There was time and space for a child to grow up in

playing between scraggly hibiscus bushes,

and hopping over rutty roads

that smelled of five-day-old urine, all on one side

of the canefield tracks, ground once blanketed

with warrior dead and sorcerers’ bones.

At the shore, the white newcomers lived

crossing themselves at sunrise and sunset

in a paradise “discovered,” jubilating

as Captain Cook who also had found the unfound natives

and their unfound shore naked and ready for instant use.

Mill Camp’s

beginnings are beginnings

one may grow to respect if not honor

because they are a man’s beginnings.

But let’s not make sentiment

the coin for the cheap treatment

some got—and others enjoyed handing out.

Let’s call the fair, fair.

What may have been good, good enough

because it was there,

like space waiting for time to fill it up

(while we were looking elsewhere);

nevertheless, plantation worlds

enjoyed their own tenors:

ghettos of mind, slums of the heart.

Albert Wendt

THE KO’OLAU

1.

Since we moved into Mānoa I’ve not wanted to escape

the Ko’olau at the head of the valley

They rise as high as atua as profound as their bodies

They’ve been here since Pele fished these fecund islands

out of Her fire and gifted them the songs

of birth and lamentation.

Every day I stand on our front veranda

and on acid-free paper try and catch their constant changing

as the sun tattoos its face across their backs

Some mornings they turn into tongue-

less mist my pencil can’t voice or map

Some afternoons they swallow the dark rain

and dare me to record that on the page

What happens to them on a still and cloudless day?

Will I be able to sight Pele Who made them?

If I reach up into the sky’s head will I be able

to pull out the Ko’olau’s incendiary genealogy?

At night when I’m not alert they grow long limbs

and crawl down the slopes of my dreams and out

over the front veranda to the frightened stars

Yesterday Noel our neighbour’s nine-

year-old son came for the third day

and watched me drawing the Ko’olau

Don’t you get bored doing that? He asked

Not if your life depended on it! I replied

And realised I meant it

2.

There are other mountains in my life:

Vaea who turned to weeping stone as he waited

for his beloved Apaula to return and who now props

up the fading legend of Stevenson to his ‘wide and starry sky’

and reality-TV tourists hunting for treasure islands

Mauga-o-Fetu near the Fafā at Tufutatoe

at the end of the world where meticulous priests gathered

to unravel sunsets and the flights of stars that determine

our paths to Pulotu or into the unexplored

geography of the agaga

Taranaki Who witnessed Te Whiti’s fearless stand at Parihaka

against the settlers’ avaricious laws and guns

Who watched them being evicted and driven eventually

from their succulent lands but not from the defiant struggle

their descendants continue today forever until victory

3.

The Ko’olau watched the first people settle in the valley

The Kanaka Maoli planted their ancestor the Kalo

in the mud of the stream and swamps

and later in the terraced lo’i they constructed

Their ancestor fed on the valley’s black blood

They fed on the ancestor

and flourished for generations

Recently their heiau on the western slopes was restored

The restorers tried to trace the peoples’ descendants in the valley

They found none to bless the heiau’s re-opening

On a Saturday morning as immaculate as Pele’s mana

we stood in the heiau in their welcoming presence that stretched

across the valley and up into their mountains

where their kapa-wrapped bones are hidden

4.

The Ko’olau has seen it all

I too will go eventually

with my mountains wrapped up

in acid-free drawings that sing

of these glorious mountains

and the first Kanaka Maoli who named

and loved them forever

Michael McPherson

DOUBLE MAILE LEI

You are timid when I lift it

over your burning auburn hair,

twining two strands together

as if these leaves were lovers

inseparable by distance and time,

twin vines from a white mountain.

I chattered while your friend sat

stone faced and distracted across

the table, telling how these leaves

hold their scent even dry as dust,

but a frightened maître d’ in Portland

balked upon my entry—we don’t wear

leaves here, sir, he said, and gently

I conjured distant seas in naked calm,

deep as azure and steeped in centuries

of trade wind whispers in kukui groves,

a sound like singing until we find peace.

It might have been my best London suit,

pinstripes subtle as those golden strands

at your temples, or perhaps this caress

of far sirens may waive our entry then.

Give this to your mother, so her mountains

beyond her vast expanse of dancing light

may touch mine, fool who fears not gold

nor diamonds bright, for his heart is full

with tropic nights too warm for questions.

I dare not ask you where they go, chords

to carry their scent of Heaven when we rise.

Wayne Kaumualii Westlake

GRANDFATHER WAS A STRANGE MAN

my grandfather was a strange man:

an old-time intellectual, a german

runaway, steamship stowaway to

mexico then legged it to frisco

then freightshiped across the sea to

lahaina, maui. . . . i mean

my grandfather was a strange man;

he worked the sugar plantation

a luna, but not a brutal nazi like

so many—no i said

my grandfather was a strange man:

he married a hawaiian even, unheard

of then—a dirty hawaiian—a HEATHEN!

and he let me run around naked

in the Sun and insisted my hair grow

long and blond, like ‘gorgeous george’ . . .

my grandfather was a strange man:

he’d laugh a lot—just a baby we’d ride

the cane trains all over beautiful maui;

ah the good old days!—retired he’d listen

to the radio, news of his dying years—

his nose bled one day and wouldn’t stop—

he didn’t say much, smoked a lot

and died frosted white, like a neon light

in a hospital, somewhere in honolulu,

skin and bones, wasted—i took the phone

call from the hospital and knew and handed

the phone to my mother: i knew it first—

my grandpa died. . . .

my grandfather was a strange man:

at the funeral it was strange—

everyone was crying (no one knew him)

and i so young just stood there staring

at the gravemound and knew, ULTIMATELY

and FINALLY: i’d never see my grandpa

again—‘so this is where the long road

ends?’ too young, i learned the TRUTH . . .

my grandfather was a strange man:

i think about him by the stormy sea

twenty years later—still wearing his

old worn shirt—torn, ragged, threadbare—

held together with coconut leaf—

my grandfather was a strange man;

his old shirt still keeps me warm . . .

Imaikalani Kanahele

Dana Naone Hall

NIGHT SOUND

Waking at night from a dream of my father

dead even in the dream.

He ate handfuls of dust scooped from a fireplace

and we drew him to a mirror to show him,

show ourselves that he no longer had a reflection.

I see the heavy patterned curtains

on the windows of my childhood,

their color deepening into darkness.

Moonlight glows on my bed.

From the next room the sound of

my father grinding his teeth in sleep.

Craig Santos Perez

RINGS OF FIRE

Honolulu, Hawai’i

He host our daughter’s first birthday party

during the hottest April in history.

Outside, my dad grills meat over charcoal;

inside, my mom steams rice and roasts

vegetables. They’ve traveled from California

where drought carves trees into tinder—“Paradise

is burning.” When our daughter’s first fever spiked,

the doctor said, “It’s a sign she’s fighting infection.”

Bloodshed surges with global temperatures,

which know no borders. “If her fever doesn’t break,”

the doctor continued, “take her to the Emergency

Room.” Airstrikes detonate hospitals

in Yemen, Iraq, Afghanistan, South Sudan . . .

“When she crowned,” my wife said, “it felt like rings

of fire.” Volcanoes erupt along Pacific fault lines;

sweltering heatwaves scorch Australia;

forests in Indonesia are razed for palm oil plantations—

their ashes flock, like ghost birds, to our distant

rib cages. Still, I crave an unfiltered cigarette,

even though I quit years ago, and my breath

no longer smells like my grandpa’s overflowing ashtray—

his parched cough still punctures the black lungs

of cancer and denial. “If she struggles to breathe,”

the doctor advised, “give her an asthma inhaler.”

But tonight we sing, “Happy Birthday,” and blow

out the candles together. Smoke trembles

as if we all exhaled

the same flammable wish.

Donovan Kūhiō Colleps

KISSING THE OPELU

For my grandmother

I am water, only because you are the ocean.

We are here, only

because old leaves have been falling.

A mulching of memories folding

into buried hands.

The cliffs we learn to edge.

The tree trunk hollowed, humming.

I am a tongue, only because

you are the body planting stories with thumb.

Soil crumbs cling to your knees.

Small stacks of empty clay pots dreaming.

I am an air plant suspended, only

because you are the trunk I cling to.

I am the milky fish eye, only

because it’s your favorite.

Even the sound you make

when your lips kiss the opelu

socket is a mo‘olelo.

A slipper is lost in the yard.

A haku lei is chilling in the icebox.

I am a cup for feathers, only

because you want to fill the hours.

I am a turning wrist, only

because you left the hose on.

Heliconias are singing underwater.

Beetles are floating across the yard.

Craig Santos Perez

ginen SOUNDING LINES

remember just dad

tied an old tire to

a metal fence pole

so [we] could practice

pitching—o say can you hear

the hollow sound when

the baseball strikes

rubber—the rattling when

it strikes wire—or

that perfect sound—

speak english only—

when [we] strike the pole

through the center of—o

say can you remember

just little league—barrigada

“tigers”—black and gold

uniforms—red seams—

my brother played for father

duenas memorial high school

“friars”—maroon and gold

uniforms—to pledge allegiance—

[we] collected american

baseball cards and cheered

for the “bash brothers”

in “oakland”—near where

brian moved for college blue

skies—the coliseum was

an island—green and

gold uniforms—white

bases—[we] stand

to sing the national

anthem—o say

can you see

[us]—what follows

your flag?

Kalehua Kim

MEMORY SONNET

Although I have come back for the summer,

my father’s house has never been my home.

His silence, humid and thick as thunder,

hangs heavier than the sun sapped mangoes

outside my window, their dense, orange flesh

sweating sugar, needing conversation.

When I ask him what he remembers best

about meeting my mother, he smiles then,

revealing only one of his dimples,

and says, “We met at da bus company,”

Something so benign, something so simple,

I’m surprised when he goes on suddenly,

“She used to sing, yeah? Ho, da voice she got,

in da house, in my head, an in my haht.”

MY FATHER’S SONNET

All the drivahs on da buses knew yo maddah.

She worked da desk, yeah? Whea dey check in,

an she was attractive, so we knew her.

I remembah yo Uncle George, I remembah

him from City and Country, and I knew she

was George’s sistah. So was easy fo’ talk to her.

I wen ask her out fas kine, I nevah like nobody

go out wid her but me. I cannot remembah

whea we went, maybe bumbay we went fo’

drinks or someten’, was long time.

Yeah, she used to sing. All da time, me an

yo braddahs, would hea her. Bumbay, I couldn’t

tink fo’ her voice all ovah da place.

In da house, in my head, in my haht.

MY MOTHER’S SONNET

Your father said he wanted to be free.

The boys were pitching tents in the back yard,

setting down stakes, building kingdoms in trees.

You were there, wearing a green leotard,

princess slippers, with a tutu in hand.

He and I sat at the dining table

where I fidgeted with my wedding band,

where he rewrote our family fable.

I want to be free. I heard him say it

again and again in my mind – it took

me years to understand, then to admit

that marriage wasn’t like a story book,

an easy tale where the prince becomes king.

It’s a harmony I hope you can sing.

Brandy Nālani McDougall

WHAT A YOUNG, SINGLE MAKUAHINE FEEDS YOU

Hamburger Helper in every flavor, tuna casserole, spam casserole, spam and corn,

spam and green beans, spam sandwiches, vienna sausages, portuguese sausages, pork and beans, cooked corned beef, onions and rice,

cold corned beef, raw onions and poi, shoyu hot dog, sardines and onions, canned chili, with rice, Spaghetti O’s, with meatballs with rice, McNuggets, Cheeseburger Happy Meals, warm birthday cake straight from the microwave, Rice Krispie treat Easter Eggs with your name in frosting, Lucky Charms, Fruity Pebbles, Cocoa Pebbles, Campbell’s Tomato soup, Chicken Noodle and Chicken with stars, saimin with egg, fried egg sandwiches, fried bologna, fried bananas, fried pork chops, fried spam, and fried fish or dried fish from Uncle— no matter which Uncle— you eat whatever Uncle brings.

Mahealani Wendt

RESILIENCE OF THE RED LA’I

A Hawaiian Transplant

It’s not as though I want to kill you; I don’t. Even if I wanted to, it seems I can’t. No amount of not watering, no re-potting, not fertilizing, no transplanting, not nothing, can kill you.

It is February, 1969. It is a cold winter morning at the corner of Fabens Road and Harry Hines Boulevard just outside of Dallas. I am standing at the stop across Penter’s Drive-In, waiting for the 4:30 a.m. bus to Chapel Hill. Ova Harlan lives there in a red brick house with central heating and A.C. in the summer. She is a God-fearing Pentecostal who watches my girl while I’m at the Travelers Insurance Company, 16th floor, First National Bank Building downtown.

I was lucky to get that job in the steno pool. They started me at two-seventy-five a month and if I do good I’ll get a raise to three hundred next year. They got efficiency experts come in and they’re real strict. Being on time, no lollygagging or socializing, is number one. I need this job to support me and the kids.

I often linger at Ova’s house when I go to pick up Lei after work. It’s hard to go back out into that cold—I’ll never get used to it. In the summer, it is an oven out there, and Ova don’t mind me hanging around too much. At home we got one gas heater in the parlor and a ceiling fan we turn on summers. They don’t help much.

I am holding Lei’s hand. She is almost two. She has got on the little red mittens that match her new winter coat. She could do with a knit cap but I can’t afford one right now.

I got Kai in my arms, he’s six weeks old. He don’t cry, don’t give no trouble. He’s sleeping, bundled up good. He has got on a warm flannel pajama sack, light blue with little yellow giraffe designs all over it. It ties under the legs. I got his diaper bag with six bottles of formula and a powder blue huggy bear slung over my shoulder. Lei’s bag with her change of clothes and other stuff is over that shoulder too. Lei somehow still manages to suck that mittened right thumb while clinging to Miss Dolly.

The air is white and shivery. The ground crackles as we shift our feet in place to keep warm. Lei has got white leggings on and little black shoes I bought on sale at Howard’s.

The bus is late and I’m worried about getting to work on time. Me and the kids have been standing out here in the dark a good forty minutes. Lei has begun whimpering she’s cold but I tell her to hush up.

The kids’ daddy got the Camaro. He came home the other night and said if I didn’t get the hell out and take the kids with me he’d bring his girlfriend home and fuck her right there in our bed.

And furthermore, no way in hell was I getting the Camaro, even though he works right down the road at Roseland Landscape & Nursery. He’s just talking crazy again but I did like he wanted, took the kids and got out. His girlfriend’s name is Sara. She’s in the peace movement and way smarter than me.

I’m far from home. My first time, really. Married out of high school and followed him to Texas. Got no family here, no one to speak of.

I don’t dwell on troubles. Main thing I gotta make sure I get myself to work on time, and I still gotta take another bus ride after dropping Lei off at Ova’s. Gotta get clear across to Oak Cliff. Reason I catch a bus clear over to Oak Cliff is Ova don’t watch babies. It took awhile, but I found Miss Ella Hildreth, and she seems like someone I can trust with Kai. You don’t want to be worrying if your kid is okay when you are at work.

Here comes the Chapel Hill bus at last! I shift baby Kai so he is securely cradled in the crook of my left arm. I adjust the bags over my shoulder and grab Lei’s left mittened hand. All of a sudden she slips and falls, let’s go a loud wail. I jerk her by the hand up off of that icy ground. “Get up! Stop that crying! She keeps it up and I give her a hard slap. “Stop it!”

That’s when I notice the large gash under her right knee. Her white leggings are soaked with blood. Horrified, I see a large jagged shard of glass on the ground, bloodied remnant of a broken bottle I hadn’t noticed earlier.

The bus pulls up and I quickly hoist Lei onto my right shoulder. We get on the bus. I tell the startled driver and passengers within earshot she is fine. We just need to get to where we’re going, is all. My mind is racing trying to figure out what I’m going to do. I feel like shit I yelled at her and slapped her but I can’t think about that now. The bus driver looks uneasy but my voice is commanding and calm: She’s fine. I got it under control. Just keep driving. No cause for alarm. No need to call anybody. We’ll be fine.”

In full view of other bus passengers I reach into the diaper bag, pull one out and fashion a kind of tourniquet to staunch the bleeding. Baby Kai stirs. I pull out a bottle and feed him while whispering in Lei’s ear, “Mama’s sorry. Mama’s sorry. You’re going to be okay sweetie. Don’t worry. You’re going to be okay.” Kai falls back asleep and I cradle the two, fighting back the tears.

It is a half-hour bus ride to Ova’s Thankfully when I get there she immediately takes charge and sends me on my way. I write the note authorizing her to get medical treatment for Lei and pass on the insurance card. I change Kai’s diaper while Ova takes Lei to Methodist Hospital Emergency Room.

I am standing at the bus stop outside Ova’s I got an hour and a half to get baby to Ella Hildreth’s in Oak Cliff. I hope I make it to work on time. Could mean my job.

At the emergency room Ova sees to it that Lei gets stitched up proper. Like I told Lei, she’ll be fine.

Lehua Taitano

HEART, AS BLACK PHOEBE

Stream-side the meadow’s edge,

an open mouth

loops a script above the grass

tips.

A cursive most legible

dusktimes, or

when wet earth warms

to burst of hatch-

flitter.

An old god will say

bright pure radiant.

Hood of soot, the heart will say

persist persist.

Love is a dark calligraphy

brushed upon the sky.

Brandy Nālani McDougall

HOW I LEARNED TO WRITE MY NAME

It is 1981 in Kula,

and my father, cloudy and high on booze

and pakalolo, for all his love songs

of rain and mountain mist, is unable

to stay. My mother, unable to leave

him, showers during his frantic search

through her purse for money, clattering loose

change against house keys, for any green bill

with a face. As an afterthought, he turns,

concerned now with my witness, young eyes. Hunched

over the kitchen table, I scribble

nonsense. He bribes, “I’ll give you a dollar

if you don’t tell.” I won’t. But I pretend

not to hear him, going on with the scratch,

scrawling the illegible string of loops

I insist is real writing. He doesn’t

bother to yell. He has no time for it,

knows he must leave before the sound of warm

water, unsteady thumps against the tub

and her skin, stops.

I knew there were stories there, staring down at the coil of e’s.

I had just written—a bouncy ocean,

a black curly hair—that this was the start

of important work. At the paper’s top,

there was my name, full, each letter composed

of dots for me to connect for homework.

My finger shadowed each sharp corner, whooshed

over straight lines and curves, almost-circles

and space—slow and careful gestures before

the pencil’s touch. Then, holding the bitten

roll of yellow wood and lead, I pressed down

hard to make a mark. Sighing with each glide,

I worked, writing through the door’s dull thud

behind him when he left, right through the wash

of swallowed tears behind the bathroom walls.

There was only this thrilled, measured motion:

my young hands threading dots into letters,

the fullness of my name, its shape, shouting.

Christy Passion

HEALING

When you left

it was a drier, brighter summer

than I would have liked. Still,

a world.

I sleep uncomfortably

in the heat, in the light, nowhere

to shield myself from the normalness

of things—

a foam cup of lukewarm coffee,

in the sink one dish, one fork,

folded laundry not yet put away.

Time is sturdy here,

facts remain facts

and the beasts of my imagination slowly

retreat to their caves.

I catch myself waiting

for another storm, for the thunder,

for an unexpected hallelujah

that would make me shake

or at least blink

but everything goes on

telling me—no harm done.

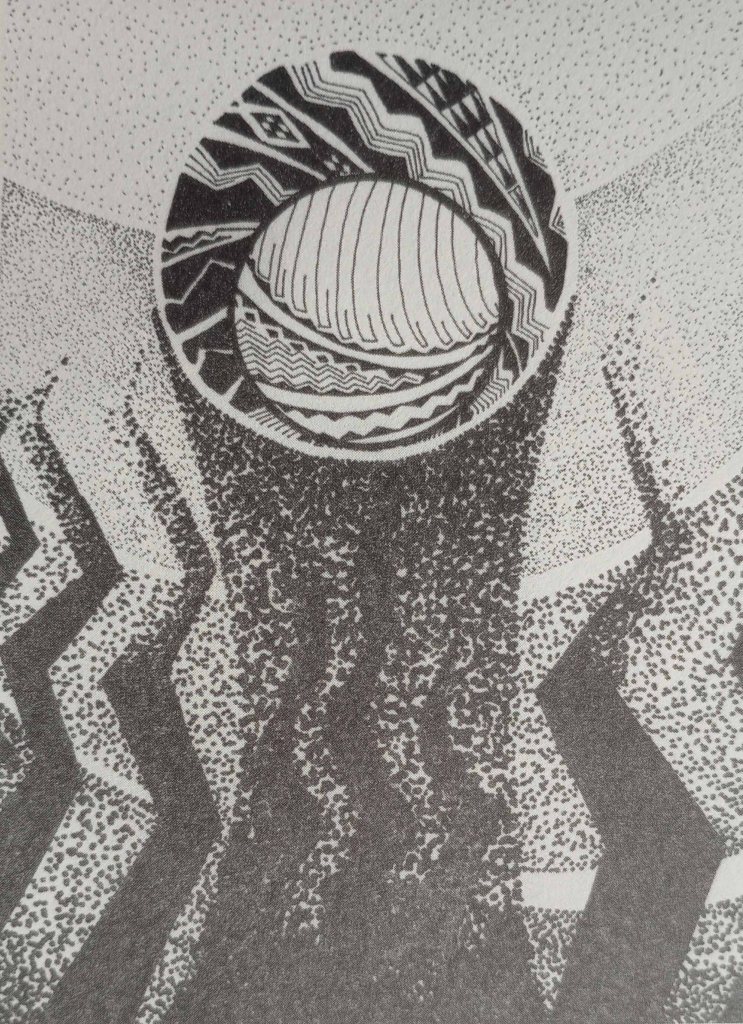

Imaikalani Kalahele

Kristiana Kahakauwila

ELEGY

Still aglow after intimacy and each bright ring

interrupts a romantic scene. My bedmate

turns, pretends not to notice caller ID.

Am I interrupting? Is dinner on?

Your voice is practiced calm. My grandmother,

you say, gone at eighty-three, a good life,

comfortable in a ripe peach way. So I

search platitudes: at least she went at home,

in her sleep. Like she wanted, you agree,

though we both know she did not want to –

In protest of death your dad refuses

to eat, and your mom, prayerful, wants only

holy things, but you know the soft rustle

of bed sheets. I’m sorry, I say to you,

and my lover returns to bed, all sweet.

What I don’t say is: your cancer scares me.

Or, better her life than yours. Or, I want

only the good parts. Selfish as I am

I am cradling his face when you tell me

you still love me, and I know then all

that will come. What is grief if not protest?

What is life if not a body able

to return in grace, in apology?

Kalehua Kim

POLARITY

When he looks at her

he remembers her in the shower,

shampoo suds trailing down

her back, between her cheeks

to her inner thighs.

When she looks at him

she tastes cigarettes

and golden apples.

“You don’t talk like this with

your friends? He asks, meaning

her husband. “No,” she answers

quickly, “We agree on everything.”

He orders sweet onions,

she prefers salted pork.

They eat, tasting

only their breath.

As they walk into the

dying light of the city,

they put their lips together

to see what comes apart.

Chuck Souza

RABBIT ISLAND SUNRISE

Chuck Souza – guitar, vocals / Sam Henderson – guitar / Beau Leonidus – bass guitar Greg Kekipi -‘ukulele / Kevin Daley – drums / Mike Paulo – soprano sax / Creed Fernandez – congas, percussion / Kurt Thompson – keyboards

Leialoha Apo Perkins

THE SPECTRAL BRIDES OF HA’ATAFA: A PHANTASY

(For Kele who saw them and for Sarah who was there to see them too)

Singing of water, of waves breaking into curls rolling to light,

the spectral brides of Ha’atafa glide, wind surfing

over subterranean terraces

over mountainous reefs that glitter back

like black mirrors of sea.

The brides must win for bridegroom

any young man who sees.

Tacking landward, they swerve trailing spume veils

as they rise. They sing as to a lakalaka, a dance.

Their songs rake the chasms

the seaweed forests, sound tracked

to ancient bridal chambers

under the sea.

The sun at its meridian looks down, down, down.

A wind rises, then shifts, colluding past noon.

The brides mount to their horizons

for the waves of a lover-to-be.

He must surf from these bars, golden to eyes watching the sea.

He must know kava.

He must hear drums.

He must dance

as he drinks

entranced

by the pitch

by the fury

of white spectres

that are charmed brides of the sea.

Imaikalani Kalahele

Dana Naone Hall

GIRL WITH THE GREEN SKIRT

She walks down the road,

her green skirt floating around her knees.

The men she passes peel off their shirts

and jump into her wide green hem.

She keeps walking, her skirt

clear as the surface of a pond.

Now they hold their arms out from their sides

like the branches of a tree, but no one is fooled

when the birds fly past them and nest

in the green forest of her skirt.

Unaware of the hot wind swirling around

the cool skirt keeps going.

The men following behind are thirsty

for the water of crushed leaves.

Falling into the deep grass

they want to live with green forever.

Brandy Nālani McDougall

RED HIBISCUS IN THE RAIN

Though the red fire-flower shivers with each tickle

of water, her stigma hangs above her like a flare to catch

a pill of pollen in her mouth, by chance. You ask her why

and listen closely, as she begins the story of her birth—

from calyx to pistil, filament to corolla—opening the folds

of her thin-veined petals to reveal the light deep in her throat.

He nuku, he wai ka ’ai a ka lā’au.

0 ke akua ke komo, ’a’oe komo kanaka.

A chant of night falls from the clouds overhead and she closes,

drawing the fire inside her petals, out of reverence for the stars.

Imaikalani Kalahele

Kalehua Kim

MAKALI’I AND THE STARS THAT FOLLOWED

It was a net of stars she struggled to lift,

her belly ready to spill its light.

Her belly ready to spill its light

she tipped like a cup, ready for release.

She tipped like a cup, ready for release,

ready to see the crown of her child’s head.

Ready to see the crown of her child’s head,

like the cluster of stars she saw months before.

The cluster of stars she saw the months before

did not prepare her for the long, dark wait.

Not prepared for more longing or darkness,

She pushed until she broke open with light.

She pushed until her child broke into flight,

a net of stars she struggled to gift.

Albert Wendt

IN HER WAKE

I walk in her wake almost every morning and afternoon

along the Mānoa Valley

from home and back after work

In her slipstream shielded from the wind and the future

I walk in her perfume that changes from day to day

in the mornings with our backs to the Ko’olau

in the afternoons heading into the last light as it slithers

across the range into the west

She struts at a pace my bad left knee

and inclination won’t allow me to keep up with

And when I complain she says You just hate a woman

walking ahead of you

No. I hate talking to the back of your head

I’m the Atua of Thunder she reminds me

when my pretensions as a Samoan aristocrat get out of hand

So kill my enemies for me I demand

Okay I’ll send storms and lightning

To drown and cinderise them

Do it now I beg

I can’t I’ve got too much breeding to act like that

(How do your cure contradictions like hers?)

She loves Bob Dylan the Prophet of Bourgeois Doom

And this morning I swam in his lyrics as she marched ahead singing:

Sweet Melinda the peasants call her the goddess of gloom

She speaks good English

And she invites you up into her room

And you’re so kind

And careful not go go to her too soon

And she steals your voice

And leaves you howling at the moon . . .

Yes for over a year I’ve cruised in her perfumed slipstream

utterly protected from threats

She’ll take the first shot or hit in an ambush

And if a car or bike runs headlong into us

my Atua of Thunder with the aristocratic breeding

will sacrifice her body to save me

By the way she nearly always wears her favourite red sandals

as she like Star Trek forges boldly ahead singing Dylan songs

and me wanting to howl at the Hawaiian moon

Wayne Kaumualii Westlake

TWO BAMBOOS

Haunani-Kay Trask

LOVE BETWEEN THE TWO OF US

1.

because I thought the haole

never admit wrong

without bitterness

and guilt

without attacking us

for uncovering them

I didn’t believe you

I thought you were star-crossed

a Shakespearean figure

of ridiculous posturing

you know, to be or not to be

the missionary rescue team

about to save

a foul, “primitive’ soul

with murder

in its flesh

11.

We all know haole “love”

bounded by race

and power and the heavy

fist of lust

(missionaries came

to save

by taking)

how could I possibly believe?

why should any Hawaiian believe?

but it is a year

and I am stunned

by your humility

your sorrow for my people

your chosen separation

from that which is haole

I wonder at the resolve

in your clear blue eye

111.

do you understand

the nature of this war?

Imaikalani Kalahele

Albert Wendt

SHE DREAMS

Nearly always she remembers her dreams vividly

At breakfast this morning she recalled how she was flying

through a noiseless storm across the Straits for Ruapuke and her father

who was sitting on his grave in their whānau urupā wearing a cloak of raindrops

and she looked down and back at her paddling feet

and saw she wasn’t wearing her favourite red sandals

She stopped in mid-flight in mid-storm and called Alapati get me my saviours!

Woke and didn’t understand why she’d called them that

It’s been about thirteen years and that makes you the man

I’ve stayed the longest with she declared unexpectedly

as we cleared the breakfast dishes

To her such declarations are so obvious and like raindrops

you can flick easily off a duck’s back

but for me it will stay a nit burrowing permanently into my skin

I won’t understand why

If I tell her that she’ll probably say You love guilt too much

You read too much into things and need someone to blame

So shall I blame her for staying thirteen years and plus?

For not wearing her saviours and reaching her dead father

who would have taken off his fabulous cloak of rain and draped it around her?

Shall I blame her for not having me when we were young

and we could have been together much longer?

Or shall I as usual just let it pass

content that I am blessed to be with her

and in her dreams one day she and I will fly together

through the voiceless storm to Ruapuke and her waiting father?

She will be wearing her saviours

and we will arrive safely

Imaikalani Kalahele

John Dominis Holt

THE POOL

It was perhaps as large as a good-sized house. It tended to be round in shape. At the far southern end of Kawela Bay, it sat open to the wind and sun. Scattered clumps of

coconut grew around it, splashing shade with the look of Rorschach inkblots here and there at the edges of the water.

Freshwater fed into it from underground arteries, blended with warmer water pushed in by the tide from the sea through a volcanic umbilical cord. “The lagoon,” as we called it, had a definitive link to the sea, being joined as it was by virtue of this unique tubular connection.

We were always afraid of the pool. For one thing it was alleged to be so deep as to be way beyond anyone’s imagination–like the idea of endless space to the universe or

the unending possibilities of time. Its dark blue-green waters were testament to the fact of the pool being deep according to our elders. We accepted their calculation,

but not entirely. It was deep to be sure, but not depthless.

Within the pool, huge ulua, a local variety of pompano or crevalle, would suddenly appear in ravenous groups of three or four, chasing mullet in from the sea. Once in

the confines of this small body of water the mullet were no match for the larger, carnivorous predators. Ulua could grow to the size of three or four feet and weigh nearly a hundred pounds. The mullet feasts by ulua in the pool were wild and unpleasant scenes. We would watch as children, both enthralled and frightened, as mullet leaped for their lives in glittering silvery schools of forty or fifty fish, some to fall with deadly precision into the jaws of the larger fish. The waters swirled then and sometimes became bloody. The old folks said this would attract sharks. They would wait at the opening of the tube in the ocean to prey on the ulua, whose bellies were now fat from feasting on mullet. These tumultuous invasions were not frequent, but they were reason enough to keep us from swimming in “the lagoon.

Perhaps most fearful to us, were the tales we heard offered by assorted adults that a goddess of ancient times inhabited these strange blue-green waters. Some knew her

name and mentioned it. I have forgotten what it was. She was said to be a creature of unearthly beauty, a queen of the Polynesian spirit world, who revealed herself at

times in the forms of great strands of limu, a seaweed, of which a special variety grew only in brackish water; her appearance depending on tides, the moon, winds, and

certain cosmic manifestations we could not completely understand because they were mentioned in Hawaiian.

I wandered for hours in the area of the pool and on the reefs nearby, with an ancient bearded sage, who was the caretaker of our family’s country retreat at Kawela.

His hut of clapboard and corrugated roofing sat near an old ku’ula, a fisherman’s shrine, half-hidden under some hau bushes. His family had been fishermen from time

immemorial. Some of his relatives lived a short distance down the coast toward Waimea Bay. Infrequent visits were made upon the old man by these ‘ohana; usually three or four young men came to consult him about fishing. His knowledge of the North Shore and its inhabitants in the sea was vast. Once or twice a year he paid a ritual visit to his family’s home down down the coast. Standing in its tiny lawn surrounded by taro patches, the little house was sheltered at the front by clumps of coconut and hala trees.

Back at Kawela, he spent hours explaining in Hawaiian, and in his own unique use of pidgin, the lore of the region, mentioning with distaste his wine drinking nephews.

I was only four or five years of age at the time. Much of his old world ramblings are now lost to me. But I do remember him mentioning that the sea entrance to the pool

was too deep for him to take me to it. He was too old now to dive to those depths. He was still able though, to secretly lead me to the ku’ula, a built-up rock shrine,

round in shape, where we took small reef fish and crustacea we had speared. We would pray; the old man in Hawaiian, I in a mixture of the old native tongue and English. It was now being impressed upon us that we must speak perfect English. The use of Hawaiian was discouraged. After prayers we would leave offerings on the ku’ula walls and walk to the pool, where more prayers were said and the remaining bits of fish thrown in as offerings to the beautiful goddess.

All these activities fell within a definite framework of time and circumstance. These were not helter-skelter rituals. I obeyed without question and I declared it untrue

when confronted by my mother–whose father, a half-white, had lived for years as a recluse in the native style in ‘Iao Valley–that the old man of Kawela was teaching me

pagan ways.

In horror one day I heard the old man say ‘hemo ia ‘oe kou lole–take off your clothes,” which consisted of a pair of chopped-off dungarees. “Hemo ia ‘oe kou lole e holo ‘oe

a i’a i ka luawai–take off your clothes and swim like a fish across the pool.” My body froze and goose bumps formed everywhere on my skin. “‘Awiwi–hurry.” I stood in

sullen defiance, thinking: he is an old man, a servant. He cannot order me to do anything–anything. “‘Au, keiki, ‘au!–Swim, child, swim! Do not be afraid. They are

with us!” I remained motionless. “Aue, he aha keia keiki kane? He kaikamahine pu’iwa paha?–What is this child? A frightened girl?”

Thoughts came to me of past fishing expeditions when I clung to the old man’s back as he dove into holes filled with lobsters and certain crabs. He would choose as time

allowed, pluck them from the coral walls, hand me two. Then, I could cling to him with only the use of my legs. In time I learned to rise to the surface alone, clinging

with all my might to the two lobsters the old man would hand to me. What excitement the first of these expeditions created! I leaped and danced around the crawling catch.

We went down for another take. Again two were brought up. On the reef above they were crushed, one then left as an offering on the ku’ula walls, the other fed to the akua in the pool. I was very young then and wild with joy.

There were other days when he took me to great caverns swarming with fish of such brilliant colors you were nearly blinded by the reds, yellows, greens, blues and stripes.

Above on the reef he would point them out to me. Patiently he named them, these reef fish, aglow in cavern waters: the lau’ipala; the manini; the uhu; the ‘ala’ihi;

the kihikihi with its black, yellow and white stripes; the humuhumu with its blue throat patch and vibrant yellow and red fins.

On one very special day, a sacred day in his life and mine as well–for I was linked to the family gods, the ‘aumakua–he took me, clinging to his back, to the vast sandy places under the sharp lava edges, on the north shore of O’ahu, where the great sharks lazed in the light of day. Breaks in the lava walls sent shafts of light to the sandy ocean floors and there we could see the sometimes-dreaded monsters rolling from side to side in harmless, peaceful rest. Shooting up to the surface, the old man would breathlessly tell me the names of this or that shark–names given them by his contemporaries. “Why names?” I would ask wonderingly. “Are they not our parents, our guardians–our ‘aumakua? Did you not see the old chief covered with limu and barnacles? He is the chief, the heir of Kamohoali’i. I used to feed him myself and clean the ‘opala from his eyes. Now a younger member of my clan does that.” I could not absorb these calm, reassuring concerns of denizens I had been taught to dread. But had I not been down in their resting place, close enough to see yellow eyes, to almost feel the roughness of their skin scraping like sandpaper across my arms? My dreams were wild for several nights and my parents, worried, held a few conferences with the old man. He was chastened, but at my insistence we went several times more to the holes under coral ledges to see the ‘aumakua lazing in the daytime hours.

And now, frozen at the edge of the green pool, I looked annoyingly at this magnificent relic of a Hawai’i that had long vanished. I loved him. There was no question I loved him deeply. Ours was a special kind of love of a man for a child. I was blond-haired. Exposed for weeks to the summer sun when we made long stays at Kawela, I became almost platnium blond. The old man was bearded, tall and thin, still muscular. He was pure Hawaiian. Blond though my hair might be and my skin fair, I was nonetheless three-eights Hawaiian. I think this captured the old man’s fancy–often he would say to me in pidgin, “You one haole boy, yet you one Hawaiian. I know you Hawaiian–you mama hapa haole, you papa hapa haole. How come you so white? You hair ke’oke’o?” He would laugh, draw me close to him and rub his scruffy beard against my face as though in doing this he would rub some of his brownness off and ink forever the dark rich tones of a calabash into my pale skin. It was love that finally led me to loosen the buttons of my shorts and kick them off and race plunging into the green pool. I swam with all the speed I could and reached in what seemed a very long time the opposite side. When I turned around, the old man was bent over with laughter. I had never seen him laugh with such gustatory abandon. “Look you mea li’ili’i. All dry up. Like one laho poka’oka’o–like an old man’s balls and penis. No can see now.” He pointed and made fun of my privates, shrivelled from a combination of cold water and fear. I turned away from him and raced home, naked.

Four days later I walked past the pool, across the sharp lava flats to the old man’s hut. Flies buzzed in legion. The stench was unbearable. I opened the door.

Lying face up and straight across his little bed, the old man lay in the first stages of putrefaction. Sometime during my absence the old man had died. At midday?

In the cool of the night? In the late afternoon, the time of lengthening shadows and the gathering of the brilliant array of gold-orange and red off the coast of Ka’ena

to the south facing the sea of Kanaloa? When did the old man die? Why did he die? Tears begain to stream down my cheeks. I shut the door of the shack and went to sit in the shade of the hau branches near the ku’ula–my heart was pounding so I could hardly breathe. What should I do? Tears continued to roll in little salty rivulets down my cheeks. I could taste the moisture when it entered my mouth at the corners of my lips. What should I do? Some instinct compelled me not to go home and tell my family of the death of the old man and the putrefaction that filled the cottage. Perhaps I was too stunned–perhaps it was perversity.

The family was gathering for a large weekend revel. Aunts, uncles, cousins–all the generations coming together. Usually I enjoyed these congregations of the family.

There would be masses of food, music, games and great lau hala mats spread on the lawn near the sandy beach. Someone would make a bonfire and the talk would begin. I would sit at the edges of the inner circle of elders as they ruminated on past events. Old chiefs, kings, queens, great house parties–scandals and gossip of one sort

of another would billow up from the central core of adults and leap into the air like flames. I took in the heat of this talk and greedily absorbed my heritage for they

spoke of family members and their circles of friends, mostly people from royalist families, the Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian aristocracy during the last days of the

Monarchy. I heard of this carriage or that barouche or landau, this house or that garden, this beautiful woman in love with so-and-so, or that abiding “good and patient” soul whose handsome husband dashed about town in a splendid uniform, lavishing on his paramour a beautiful house, a carriage and team, and flowing silk holokus fitted finely to her ample figure. O, the tales that steamed up from those gatherings on lau hala mats on the shores of Kawela!

One of my great-aunts, an aberration of sorts, came once in a while for the weekend. She brought a paid companion and her Hawaiian maid. She looked like Ethel Barrymore and talked with an English accent. Her gossip was spicy, often vicious, and I loved it. She fascinated me as caged baboons fascinate some people who go to zoos. She was also forbidding. I thought she had strange powers. Often the old man had joined us during these family gatherings, and I would sit on his lap until I fell asleep. There was something of great warmth and unforgettable charm in these gatherings. Even as the talk raged over romances, land dealings and money transactions long passed, I enjoyed hearing about them and loved everyone there, particularly those who talked. There was an immense feeling of comfort and safety, of lovingness for me on those long nights of talk.

But now under the hau branches I scorned my family. I hated them. I held them responsible, for some unknown reason–a child’s special reason I suppose; inexplicable

and slightly irrational. I decided not to tell them of the old man’s death but to run down the path along the beach to the house where some of his relatives lived. I

would tell them. They must rescue him from his rotting state; they must take him from the tomb of his stench-filled shack. I ran down along the beach, sometimes taking

the path pressed into winding shape from human use in the middle of grass and pohuehue vines. The men were at home, mending fish nets. This was a good sign. I ran to the rickety steps leading upward to the porch where they sat working at their nets. “The old man is dead,” I said forcefully. One of the young men looked down at me. “Make?” “Yes, he’s make. His body is stink. He make long time.” They put down their mending tools and came together at the top of the stairs. “How you know?” one of them asked. “We just came back from Punalu’u I went to the old man’s house. I saw plenny flies. I open the door and see him covered with flies. It was steenk.” I spoke partly in pidgin to give greater credibility to my message. They fussed around, called into the house, held a brief conference and faced me again. “You wen’ tell anybody?”

“No, nobody.” The four men took the path at a run.

I was under the hau bushes, catching my breath, when they flew past me heading back to their house. I sat for what seemed like hours in the shade of the hau. My sister appeared at the side of the pool. I ran to fend her off. She caught the stench from the shack. “Something stinks.” “The old man has fish drying outside his shack.” “Where is he?” “Down on the reef fishing.” “When are you coming home?” “Pretty soon.” “Mamma is looking for you–Uncle Willson is here with those brats,” she referred to his adopted grandchildren. Uncle Willson was a grand old relic. Something quite unreal. He was brimming always with stories of the past. “Aunt Emily has arrived with Miss Rhodes and that other one,” my sister added, alluding to the maid whom she hated. The cottages would be bulging and perhaps tents would be set up for the servants. My sister swung around abruptly and took the path back to our cottage. She was always purposeful in her movements. “Tell Mamma I’ll be home soon and kiss Uncle Willson and Aunt Emily for me.” “Don’t stay too long. You’ll get sunburned.”

I walked past the pool. It seemed purer in its color today. Deep blue, deep green. I was crying again. The stench filled the air with a stronger, punishing aroma as the sun rose high and began the afternoon descent beyond Ka’ena Point. I walked along the reef; the tide was rising. I peeked into holes the old man had shown me, watched idly the masses of fish swimming in joyous aimlessness it seemed. What ruled their lives? There was life and death among them. They were continually in danger of being devoured by larger fish. Some grew old and died, I suppose, they die of old age. I looked back at the shack and shook my fists. The old man’s nephews had returned with gleaming cans. They poured the liquid from them all around the little shack. I rushed back to the hau bushes as two of them threw lighted torches of newspaper at different spots. Soon the shack was in flames which leaped into the sky; as the dry wood caught fire, it crackled furiously. The flies buzzed at a distance from the blaze as though waiting for it to die down. The heat was intense. The smell of burning rotting flesh unbearable. I ran from the hau bushes toward the pool. One of the men saw me and yelled, “Go home, boy! Go home!” “Git da hell outa heah, you goddam haole!” another one shouted. I was angry and stunned in not being accepted

as Hawaiian by the old man’s nephews.

I ran around the pool at the side we seldom crossed. My family was massing nearby to watch the fiery spectacle. “What’s happening, son?” my father asked with more

than usual kindness. I ran to my mother and hugged her thighs. “The old man is dead. I found him. He was stinking. I ran down to tell his family.” “And now the

bastards are burning him up,” my father said. “It’s against the law.” Aunt Emily had arrived on the arms of her companion and maid. Her handsome face pointed its

powerful features to the center of the burning mass. “What is happening? she asked in Hawaiian. “Our caretaker died. Been dead several days. The boy found him.”

“What are they doing?” “It’s illegal. They’re cremating him without going through the usual procedures.” Aunt Emily blasted forth with a number of her original

and unrepeatable castigations. Everyone listened. They were gems of Hawaiian metaphor.

Uncle Willson and his man servant arrived. “The poor old bastard finally died. He was the best fisherman of these parts in his younger days. No one could beat him.

As a boy he was chosen to go down to the caverns and select the shark to be taken to use for the making of drums. His family were fishermen. One branch was famed as

kahunas. He was a marvel in his day.” “But Willy,” Aunt Emily was saying in a commanding tone. “Those brutes are burning his body. The boy here says it was rotten. He’d been dead for several days. The whole thing’s a matter for the Board of Health authorities. The police should be called.” “No, no! I screamed.

“Emily dear,” Great Uncle Willson intervened. “He is one of us. His ‘ohana, those young men are a part of us. Leave them alone. They are doing what they think best.”

I had gone from my mother to my nurse Kulia, a round, happy, sweet-smelling Hawaiian woman. “No cry, baby. No cry. We gotta die sometime. Da ole man was real old.” “Not that old,” I whimpered. Aunt Emily cast one of her iciest looks at me. “Stop that snivelling! Stop it this instant! What utter foolishness to cry that way

over a dirty, bearded old drunk!” She turned to my mother. “This child was allowed to be too much with that old brute. I think his attachment was quite unnatural–quite unnatural.” “Another one of your theories, Aunt Emily?” my mother snapped. “Not a thing but good common sense. Look at him clinging to Kulia and whimpering like a girl.” Kulia took me away. We walked on the beach. How I hated Aunt Emily’s Ethel Barrymore profile and her English accent.

Late that day, in the early evening, the old man’s nephews came back and carried off his charred remains in the empty cans of kerosene. No one ever found out what

they did with them.

When did the old man die? Why did he die? This I will never know. We called him Bobada, but I remember from something Great Uncle Willson said on the night the shack was burned that Bobada’s real name was Pali Kapihe.

Carl Pao

Michael McPherson

MALAMA

On the Puna coast, near the easternmost tip of

the island Hawaii, in a grove of tall ironwoods

planted early in this century stands a lava and

mortar marker, similar in shape and height to older,

mortarless markers found on trails which cross the

flanks of Kilauea Volcano, and bearing this

inscription:

MACKENZIE PARK

IN MEMORY OF

FOREST RANGER A.J.W. MACKENZIE

OCTOBER 1, 1917 – June 28, 1938

1

What angry ghosts are these

that roam the salt washed

honeycomb of corridors

through the belly of the earth,

fingering outward and down for miles

from the sea to the heart of the mountain?

Who can sleep in this grove

in the broken night, a windy

cacophony of flutes and drums,

and grinding of stones deep in the belly,

the ground trembling

as the heartbeat shifts,

and chants of the procession

as they mark again the passing of their king—

Is it any wonder then

that the campers

often in their haste

leave food and gear behind?

And from where comes

this orange glowing light

somewhere upward and ahead, around

the endlessly rounded corner in the corridor

of the dream?

The ranger slept here, long ago.

Alone he rode the two days down

from his home at Kilauea. He planted trees

in the days, trees which frame the king’s highway,

labor of prisoners in late Hawaiian times,’

and at night he lay alone by his fire

and listening to the stories on the wind

and rumblings in the earth’s belly

he was content, and slept

dreaming the warm belly of the woman

in the orange glow

from the heart of the black mountain.

2

At Kapoho the field zippered open

like the incision of a great invisible knife

and buried the town. East the blood of the land

ran burning to the sea, and covered all

but the little kuleana where an old woman

wandering alone in that darkest of nights

had found food and warmth and shelter, and today

we see it surrounded on three sides,

the tiny house and corral guarded by silent stone.

3

Mr. Mackenzie lost his life while on duty. He had

stopped his car, loaded with young trees, on a hill

to allow the motor to cool. The brake gave way,

and the vehicle started backing up. Mr. Mackenzie

reached inside for the hand brake but the car kept

moving faster. It struck a rut in the road, and Mr.

Mackenzie in turn was struck a severe blow,

apparently by the door handle, in the region of the

heart which proved instantly fatal. The car righted

itself in a few feet and stopped.

—Hilo Tribune Herald April 20, 1953

The ranger fell in the forest of Waiohinu,

the shining water. Whether by the door handle

or the hand of a man he knew is not for us

to understand, Brooks’s story remains,

told and retold, as when a fountain

for the ranger’s wife was dedicated in the park

and an account in the local paper referred

to the “freak accident.”

Whether it was then the cavern’s roof collapsed, and the ironwoods

rerooted to the floor

is not recorded either. But no one stays

all night in the park

on a new moon

and talks about it. By moonlight

a pistol is handy, as then the murderous living

stalk their prey in favorable isolation,

as in the killing of the young physician; the malice

of an apparently motiveless crime. But in darkness,

Puna darkness, a gun is nothing. Among shadows

of the corridors of stone

a man’s only weapon is his silence.

4

The sun on these sea cliffs

is the first to reach Hawaii, garland

of islands growing eastward into its rays

How bright the sun dances on this deep, deep sea,

and shines, too, on the stone monuments

to the two fallen fishermen whose lives were lost

where the blue water meets the smooth black stone,

whose bodies were swept into dark tunnels

underground, their bones now hidden in secret caves

like the old alii. So much death,

so much blood

is a part of this place—

its silence

at morning.

The wind in the ironwoods is hushed,

ghostly,

like our footsteps in the thick needles

under the trees.

5

What angry ghosts are they

that cannot sleep in such deep silence?

Do they serve the woman of the mountain

whose rage is legend

whose love is kindness to strangers

in strange, dark places? Whose blood

is stone, whose orange light glows

in blackness, black heat

glowing orange

in the spiral corridor

of the dream

dreaming heart of the mountain.

Carl Pao

Christy Passion

CRABBING AT THE OLD TRAIN TRACKS

I. K. Kaya’s Fishing Supplies

Smell of dust and old rain when you enter,

the filtered sunlight through the filmy windows up top

touching the bamboo poles, nylon nets, and wood trimmed

glass case filled with metallic lures and pink glitter squids

shimmering desire; everything as it always is.

I am here with Papa, his tanned arm outstretched

over the counter to Mr. Kaya’s, whose face

is all numbers and books, but his knuckles

are square and his palms are calloused;

they know hard work. The tin cans stripped of their labels

(were they asparagus? maybe tomatoes?)

line the edge of the aisles filled with small lead weights

and blunt spindles. Hanging on the wall

the cotton string crabbing nets we came for

patient and plain, like Pop’s gray Kangol

hanging next to the front door.

My hands run over all the different textures

carelessly I slide my feet into rubber-soled tabis;

while I half listen to the men share their truths

about fish and family. There is no need and busy here,

just a slow belonging among the Penn reels and glass floaters

centered, unopened.

II. Bait

The butchers are at home, still asleep;

the hooks for the duck and char siu empty, yet

the fish stalls are already lit, being stocked

by lean men in rubber boots carrying

soggy cardboard boxes on their shoulders

hustling in the early morning simmer.

Buckets of ice are poured onto steel tables

for the whiskered weke and wide-eyed menpachi,

each fish neatly lined up with the next

like iridescent red-bellied dominoes.

A trough of tight-lipped Manila clams

proves irresistible to touch—

Papa motions for me to hurry along

so I let them roll from my palm

back to their family, their difficulties.

He calls out to the old Chinese man

smoking at the register, counting our coins.

Assok get aku head?

Get, you like see?

Fish heads, heads as big as mine,

with their purple red lungs trailing

like party streamers, are held up for approval—

I clap as they are tossed into our plastic bucket,

lean over them to take in the blood smell,

the torpedo shape of their platinum heads,

tiny hooked teeth just inside the border of their mouths

agape, seemingly mid-prayer, their last fish words

not known to me. Bright gloss of their gelid eyes

glinting under the fluorescent lighting

fresh like the morning star, promising.

III. Old Train Tracks

The blue Nova kicks up the dry dirt no matter

how slowly we pull in, but no one makes the effort to go as far

as the old train tracks, so we don’t have to apologize.

We unload under the misplaced monkeypod tree,

lay the net flat, untangling the string from the floaters

without much talk; each tug and twist familiar, devout

and on the best of days, it stays mostly quiet

once the nets are cast then settled into the chamoised silt layers.

Julie’s tangerine bikini top flashes taut and uncompromising—

she sets up with the good beach chair a fair distance

from the bait bucket and its mob of flies.

Pop sequesters himself under the sparse shade of thorny kiawe

holding his transistor radio against his right ear and cheek.

The sticky silver knob rolls between a talk show

touting DMSO and Frank Sinatra. I keep to the middle

balancing on the last two tracks laying on the rotted wood,

click my tongue against the roof of my mouth

tasting metal in the noonday haze, waiting.

The Pacific is not beautiful here, from the land to its mouth

there is no subtle transition. Unnatural angular rocks

form the torn shoreline once heralding a red train that carried

the Queen and her entourage. It is brown here, grubbed,

a blemish of crippled waves. When I look out at her,

unending blue with white lashes blinking at the sun,

I pity these choked off inlets, still connected

but wanting to be forgotten, like widows at a bridal shower.

There is no urgency here, no desire for ascent:

Julie’s Teen Beat, her Farrah Fawcett hair, the sound of Pop

pissing behind the Nova, his white undershirt slack,

the water from the melted ice in the Igloo flecked with dirt

and suicidal gnats as I splash it against my neck.

we are not beautiful Hawaiians here.

IV. The Pull

It’s time

the only mistake now is stopping;

once the cord is touched, pull with the chest twist at the waist—

maybe it’ll be another monster like the six-pound beast

from two summers ago, pulled up right here

defiant, cutting through the net with his black striped claw

eyes on the eddy, there’s the orange floater

swaying towards the gray surface, then the metal rim—

maybe it’ll be blue crabs, soft shelled, Mama’s favorite,

newspaper spread out over the counter first then

the thwack of the butcher’s knife splitting them in two

the water’s letting go, hands keep gliding

as the cord cuts into the palm

maybe there’s nothing, that’s part of it too;

sometimes nothing’s all there is. On those days

sweat and stagnant water stink lingers on the ride home.

Nothing’s quiet as church, uncomfortable as tight shoes

Julie’s come over, gloves on, bucket in hand, arcing against

a sudden gust, her skin bright as copper on ash

Pop’s positioned on the ledge

looking into the unseeable, turns back smiling,

so I lock my legs, pull with all I got knowing

we’ll make do with whatever’s given to us.

Tamara Wong-Morrison

ALOHA IS ENDANGERED

They are counting whales

And letting loose baby turtles

Tracking monk seals

And planting only native plants

Who’s counting how many Hawaiians left?

How many Hawaiians still living off the land

Pulling ahis from the sea

Planting kalo, pounding poi?

Hard for live Hawaiian these days

Cannot hunt pig, cannot eat turtles

The kuahiwis are Nature Conservancies

Conspiracies to keep us away

More bettah shop Costco

Buy Spam, get food stamps

Collect Worst-fare

Give up, kill fight.

Imaikalani Kalahele

Dana Naone Hall

LOOKING FOR SIGNS

Aunty Alice said it first

there had been ho’ailona

ever since we took up

trying to keep the old road

from being closed in Makena

on the island where Maui

caught the sun in his rope.

The foreign owners of a half built

hotel don’t want their guests

to taste the dust

of our ancestors in the road.

They want them to step

from the bright green clash

of hotel grass to sandy beach

and the moon shining on a rocky coast.

The last hukilau in that place

was ten years ago,

but people still remember

the taste of the fish and the limu

that they gathered on the shore.

When tutu gets sick

the only thing that brings her back

is the taste of the ocean

in soup made from the small

black eyes of the pipihi.

In her dreams opihi

are growing fat on the rocks.

She is old and small now

in her bed above the blue ocean

wrapped in the veil of her dream

like the uhu asleep

after a day of grinding coral into sand.

It was at this house one Sunday

that relatives who stayed home from church

saw a cloud of dragonflies appear

over the ocean and fly through the windows.

Higher up the mountain someone else

dreamed of seeing Pele’s canoe

on the water the red sail of Honua’ula

coming toward land.

One weekend the family slept

at another beach along the old road—

the old road that is the old trail.

Uncle Charley took us all to the heiau

mauka of the beach.

From the beginning he has said

the road will not be closed.

When we came back,

Ed, one of the boys from Hana,

was standing in the shallow water

sending the sound of the conch shell

and the winding breath of the nose flute

across the channel to Kaho’olawe

through the ear of Molokini.

Later, we listened

to Uncle Harry joke with the kupuna.

Tutu was there and she stayed

all night sleeping in the sand

with the ‘aumakua all around.

The mo’o clucked in the kiawe,

while pueo flew through the dark

cutting across the path

of the falling stars,

and mano ate all the fish but one

in the net that Leslie laid.

As for us,

what is our connection to Makena?

You pointed out that we live on

one of three great rifts out of which

lava poured in ages past

to form the mysterious beauty of Haleakala.

Two gaps press in on the rim of the mountain

like a pitcher with two spouts.

Ko’olau separates us from Hana

and Kaupo divides Hana and Makena,

but there is no gap between us

and Makena lying at the bottom of

the youngest riff, where the

sweet potato vines covered the ground.

This morning, coming back along the coast,

on our side of the island

where the road bends at Ho’okipa,

I saw a cloud shaped kike a pyramid

and a car driving out of the sun.

Carl Pao

Kristiana Kahakauwila

LET US BE ANTIBODIES

In one of my earliest memories I am reaching upward, waiting to be lifted onto my father’s shoulders. We are strolling 2nd Street, a pavilion of shops and restaurants near our house in Long Beach, California, en route to frozen yogurt. Two vanilla cones: rainbow sprinkles for me, chocolate for him.

This is our weekend routine: Saturday afternoons our escape. My mother is the type to shop at health food stores even before that was a thing, to have banned white rice and cured meats from the house. No candy. No chocolate. Saturdays with my dad are different. We are a team—a team whose sport is eating frozen yogurt.

There are those Saturdays he cannot lift me atop his shoulders. The handful when he cannot lift himself out of bed. On those days his breathing is labored, the act of inhalation exhausting. My father is a severe asthmatic, and though athletic and otherwise healthy, when dust or fungi, bacteria or other pathogens enter into his body, his immune system fails to properly resist their effects.

When I’m a teenager, my dad and I turn the annual family ski trip into a father-daughter adventure. We fly to Park City for my spring break. The next year we drive to Mammoth. My mother makes the arrangements: books the condo, works the finances, tells us which shop has the cheapest rentals, and where to find the grocery store. We dutifully call her each evening but, I hate to admit, I don’t miss her. I like these days with my dad, peering into crevasses from the ski lift, following the lines his

skis make in the snow. In the evenings he cooks spaghetti with sausage or burgers with bacon. After, I study for my Advanced Placement exams while he watches baseball on the television.

My dad is kanaka maoli. Native Hawaiian. On the mountaintop, that sun so close you could lasso it, his skin turns impossibly dark. We get raccoon eyes from

our goggles. It is he and his Hawaiian friends—the ones I call uncles—who taught me to ski when I was four. Years later, as an adult, I think to ask, Why skiing? I learn

that he had never seen snow until he was in his mid-twenties. But his friends, all outrigger paddlers, needed a sport for the off-season, so they chose the most unlikely,

the biggest lark. They’ve always liked a good joke, and a bunch of Hawaiians on skis is it.

When I was a child, my mom was often asked if I was adopted. She of Norwegian-German extraction, skin so fair it burns in the first five minutes of summer. Hair a brilliant red. Her family says I have her eyes. We agree my nose is a mix

of parentage. The rest, my dad: my coloring, my mouth, my jawline. All his.

It’s not that I’m not close to my mom. I’m her in so many ways, become her more as I age. (No candy in my house, either. No bacon, to my fiancé’s chagrin.) But we are close in a way particular to mothers and daughters—as extensions of one another, we recognize in the other what we least like in ourselves.

With my father it’s different. I am his little girl. Always will be. At the movies he still covers my eyes during sex scenes. He did this recently. I’m 35. But I don’t mind being his little girl, his sweetheart. We see in each other the best part of ourselves, and so to please him is to please myself. His happiness is worth more than any other’s, because it is my happiness, too.

I used to, as a child and even adolescent, love to nap with my dad. He worked the

night shift for three-month swings, and in those weeks he would sleep during the day. He preferred a mat on the floor, rather than the marital four-post bed. The mat

was a holdover from his childhood in Hawai‘i and remained useful for finding a cool spot to rest in the midday Los Angeles heat. I’d come into the room and lie down next to him, match my breathing to his. He smelled like jet fuel—no surprise for an air-freight manager—and the husky-sour scent of his medicines, the prednisone and albuterol and other asthma medications that have been a mainstay of his, of our, life.

I described these naps recently to a friend, and I watched her expression as she struggled to overcome her concern and fear and confusion. I realized, watching her, how fortunate I have been. I associate my father and uncles with safety, warmth, the slow intake of breath. In Hawaiian, aloha means to share breath. My relationship with my father is one of aloha.

I realize this is not the case for many other women, especially those within indigenous communities. But I was gifted early with my dad, this great example of a good man, and thus my life has been filled with many good men.

During and since the election I have been thinking a lot about what it means to have a good person in a child’s life. Not a perfect person—my dad’s not perfect—but a good person. And I think having a good person in one’s life means building a foundation of self-worth, means increasing resistance to outside influences that will claim you have less value. Good people support who you are, all of you. And that support gives you strength, resilience. A good father or uncle, mom or aunt; an exceptional sibling, adopted family member or friend: They are like antibodies. It’s not that viruses or pathogens—those cruel words someone says about where you come from; the way, as a woman or person of color, you can be dismissed in a meeting; the bizarre attempts certain people make to assure you that their seeing you as less than them is a way of protecting you—cannot enter. They do enter—your body, your world, your heart. But having the right people, men and women, means you have the antibodies to resist that hurt, the strength to understand that those viral happenings are not true.

Here’s what I find so amazing about antibodies: Though they are formed in response to a single pathogen, a single sickness, they stay in your blood. They stick with you, for a lifetime, protecting you, maintaining your resistance, giving you strength, again and again and again.

When I lie next to my father, when I match my breath to his, I feel what it means to be him. To inhabit his inhalation is to inhabit his world. This is an act of empathy, of understanding. Sometimes I imagine myself as his protector, just as he has been mine. I cannot fix his asthma. I cannot take it away. But I like to think—and I suspect he would agree—that all those years of ski adventures and frozen yogurt and movies I have only viewed in fragments were a kind of resistance to the effects of his illness.

I want, in the days and weeks and years to come, to think of myself as an antibody. To be your antibody. That sounds so intimate. It’s meant to be. An antibody offers more than support—it gives protection. To be an antibody is to believe in someone else’s worth. Every one else’s worth. It’s the love of life, every life, but especially those

lives that are unequally threatened by our—our, we make them—systems, institutions, and government. It’s the commitment to fighting pathogens and to resisting their effects.